Of Monster Soup, Ghostly Maps & Men

⚠️Trigger Warning ⚠️

This episode includes discussions of bodily functions, so if you’re eating, you may want to pause and come back later. It also touches on the difficult topic of infant mortality. Listener discretion is advised.

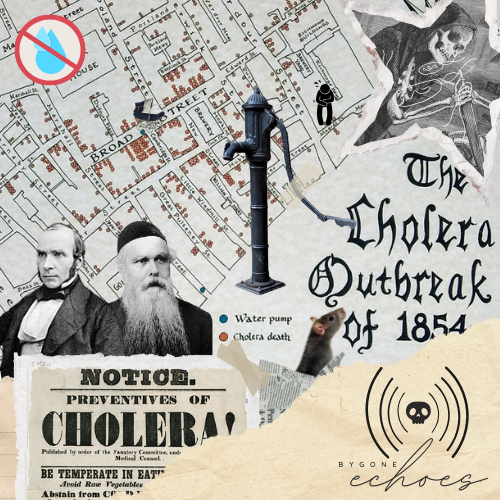

TL;DR: Victorian London in 1854 was a mess—literally. 💩 Cholera was killing people left and right, everyone thought “bad vibes” (aka miasma) caused disease, and the water was straight-up poison. 💀💧 Enter Dr. John Snow (the one who knows something) and Reverend Henry Whitehead, who teamed up to expose a killer water pump 🏴☠️ and change public health forever. It’s a story of bad science, haunting maps 🗺️, and why you should be very thankful for modern plumbing. 🚰

Welcome to Bygone Echoes, a history podcast. I’m your host, Courtney, and thank you so much for joining me! I know it’s been a while. My life lately has felt like juggling flaming swords—exciting, chaotic, and, given my lack of hand-eye coordination, hilariously disastrous. But hey, I’ve finally managed to put the swords down and I’m ready to roll! Thanks for sticking around while I wrangled the circus act that is life. I’ve missed you, and I’m so thrilled to jump back into the wonderfully weird world of history together!

Today, we’re stepping back into the grime, grit, and gloom that was Victorian London—a place where the streets buzz with city life, but also with something far more sinister.

Imagine it’s 1854. You’re walking down a narrow, cobblestone street in London’s Soho neighborhood. The sky hangs in a perpetual gray, and the air is thick with the stench of human waste, rotting food, and industrial fumes. The streets are teeming with people from all walks of life—men in top hats and long coats, women in heavy skirts, and children, some barefoot, playing in the muck, oblivious to the danger around them. But beneath the everyday bustle, there’s a palpable tension, a sense that something is terribly wrong.

That something is cholera, a deadly disease spreading through the city with alarming speed. People are falling sick by the dozens, and within days—sometimes just hours—they’re gone, claimed by a brutal and swift death.

In 1854, the cause of cholera was a mystery. Was it carried in the air? Clinging to the very clothes on your back? Or was it a punishment for moral failings? No one knew for sure. What was certain was that it struck without warning, affecting people of all ages, from the youngest children to the elderly.

This ignorance only fueled the panic. Londoners were desperate for answers, but the prevailing wisdom of the time pointed to the miasma theory—the idea that diseases like cholera were spread by “bad air”. Imagine the chaos as people tried to purify the air around them—burning incense and herbs, covering their faces with handkerchiefs, staying indoors—all in a futile attempt to escape a disease that seemed to be everywhere and nowhere at once.

In this fog of confusion, as fear and death continued to rise, two figures emerged to challenge the status quo. Dr. John Snow, a physician with a penchant for skepticism, and Reverend Henry Whitehead, a local clergyman with deep ties to the Soho community, were about to turn the world of public health on its head. Together, they would embark on a quest to uncover the true source of the cholera outbreak, leading to a groundbreaking discovery that would revolutionize our understanding of disease and shape the way we design and safeguard our cities to this day.

So, how did these two unlikely allies solve one of the greatest medical mysteries of their time? Let’s follow their trail on the ‘ghost map’ they created, a map that would uncover the deadly truth and change the course of history.

Before we step into Soho, London, in 1854, let’s zoom out for a moment and take a look at what the rest of the world was up to during this time. The mid-19th century was a period of immense change and upheaval across the globe, marked by revolutions, the rise of industrial powerhouses, and significant cultural shifts. So, we have alot to talk about!

Europe was a continent in transition, torn between old empires and new ideologies, with power struggles and social unrest bubbling beneath the surface. The Revolutions of 1848 had left a lasting impact, fueling rising nationalism and calls for social reform across the region. Meanwhile, Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire were locked in the Crimean War, battling Russia in a conflict that dominated headlines and reshaped alliances. In Ireland, the Great Famine was drawing to a close, sparking a wave of emigration that sent thousands abroad in search of better lives.

In Asia, the Qing Dynasty was embroiled in the Taiping Rebellion, a devastating civil war that would become one of the deadliest conflicts in human history. Japan, which had self-isolated for more than two centuries, was forced to open up to the West under the threat of violence from American Commodore Matthew Perry.

In India, British control was tightening, with increasing interference in local governance and cultural traditions, setting the stage for uprisings like the Indian Rebellion of 1857. The Dutch, meanwhile, were solidifying their empire in the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia), particularly in Java, after regaining control from the British in 1816 following the Napoleonic Wars.

Africa was grappling with the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade and the encroachment of European colonial powers, with resistance to French and British expansion already taking root.

The United States was driven by the ideology of Manifest Destiny, a justification for the genocidal removal of Native Americans from their ancestral lands. Entire tribes were forcibly displaced, their cultures systematically erased, and their populations decimated through massacres, starvation, and disease. Policies like the Trail of Tears epitomized the violence inflicted on Native peoples, while forced relocations to reservations ensured their continued suffering.

Meanwhile, Abraham Lincoln—not yet president—and other politicians were grappling with escalating tensions over slavery, as the nation inched closer to civil war. At the same time, innovations like the telegraph were shrinking distances, with submarine telegraph cables enabling the first rapid communication between continents. The world was becoming more interconnected, and now events in one nation could easily ripple across to others.

America’s rapid expansion depended heavily on immigrant labor. Irish and German workers, in particular, were essential to the country’s growth during the 1850s, taking on some of the hardest and most dangerous jobs in factories, mining, and infrastructure projects. They worked long hours for low pay, often in unsafe conditions, while also facing heavy discrimination. Their labor wasn’t just critical—it was the backbone of America’s progress.

It’s worth asking: how much of our history is built on the efforts of people who weren’t treated with the dignity they deserved? Immigrants, in particular, have long been the backbone of growing economies, taking on grueling jobs that others often avoid. Even today, they face many of the same challenges—low wages, unsafe conditions, and systemic inequities. Recognizing their contributions isn’t about pointing fingers; it’s about understanding that a country’s progress comes with the responsibility to value and protect the people driving it forward.

This idea of overlooked contributions ties directly into our story today. In 1854, the cholera outbreak in London didn’t just highlight the flaws in public health systems—it also exposed the ways society’s most vulnerable groups were left to shoulder the greatest burdens. At first glance, the outbreak might seem like a localized crisis—a grim but relatively small event compared to the sweeping revolutions, wars, and innovations of the era. But in reality, it was a turning point, a disaster with profound global implications that reshaped the way we understand public health and disease.

Right in the heart of London’s West End, the neighborhood of Soho covers roughly 1 square mile (2.6 kilometers). Soho started as farmland with a leper hospital nearby, became a royal park under Henry VIII, and later transformed into a residential district, growing organically into a maze of alleys.

During the Great Plague of London in 1665, a mass burial pit was created in Soho, earning it a grim reputation. The plague pit in Soho was so massive and infamous that it was said, “no foundations were laid in the area for two generations,” though in reality, development only stalled temporarily.

By the 18th century, the neighborhood flourished as a fashionable district, home to elegant Georgian townhouses and London’s growing middle class. The neighborhood was well-maintained with cobblestone streets that added to its charm and appeal.

But, in the early 19th century, things began to change for Soho. The neighborhood’s wealthier residents started packing up and moving out. The Industrial Revolution brought waves of new, often poor, people to London, all chasing better opportunities, and Soho quickly became overcrowded. As the neighborhood filled up, living conditions declined, and public health issues grew. Meanwhile, shiny new neighborhoods were popping up across London, offering modern amenities, cleaner air, and a more exclusive vibe—making them irresistible to those who could afford a better quality of life.

As those who could afford to leave Soho left, their old grand Georgian homes were snatched up by opportunistic landlords eager to cash in on the influx of new residents. These landlords wasted no time chopping the properties into cramped apartments, tenements, and shop fronts, squeezing as many people as possible into each building to maximize their profits. With little to no investment in upkeep or sanitation, these once-elegant homes quickly deteriorated, becoming overcrowded, unsanitary, and unsafe. The cobblestone roads, once smooth, had grown worn and uneven, making every step a bit of a gamble.

These homes were quickly filled by the working-class families from rural England, along with immigrants from Ireland and across Europe, all drawn to London in search of work and a better life. Jobs in factories, mills, and workshops promised better wages than farming ever could.

Soho also became a haven for political exiles during the 19th century, thanks to its central location and diverse community. French political refugees, Italian and German nationalists, and Polish and Russian exiles all found a home in Soho, adding to the neighborhood’s rich cultural scene.

London was growing fast—too fast. The city’s infrastructure wasn’t designed to support such a rapid influx of people.

Soho in the 1850s was suffocatingly overcrowded, with over 300 people per acre crammed into narrow streets and tightly packed buildings. The air was thick with foul odors, and sanitation was almost non-existent, turning the neighborhood into a breeding ground for disease.

Water, a basic necessity, was scarce and unreliable. Most residents did not have access to clean, running water in their homes. Instead, they relied on communal pumps and wells scattered throughout the neighborhood. Like, literal water pumps which I can’t even conceptualize in my mind, today, that my only water source would come from a community pump. Wild.

Anyway, the only water that most people could drink came from pumps that drew water from underground sources. These were often contaminated by the filth and waste that permeated the area. Sewage systems, as we know them today, were largely absent. Human waste was typically disposed of in cesspools—large, often overflowing pits located beneath or near buildings. When these cesspools overflowed, the waste seeped into the groundwater, turning the public water supply into a breeding ground for disease.

Waste and garbage were another major issue. With no organized waste collection, refuse piled up in the streets or into cesspits, attracting rats and other vermin. The Thames, the city’s main waterway, became a dumping ground for both industrial waste and human sewage and water from this source was commonly called “Monster Soup”. The stench of rotting food, human waste, and industrial fumes filled the air, contributing to an atmosphere that was both physically and psychologically oppressive.

For the poor and working-class residents of Soho, these conditions weren’t just unpleasant—they were a ticking time bomb. Overcrowded, unsanitary, and ignored by the city’s elite, the neighborhood was primed for disaster. And in August of 1854, that disaster struck, turning grim potential into a harrowing reality.

Think about the worst stomach ache you’ve ever had—maybe food poisoning or a stomach bug that left you curled up, barely able to move or keep even water down. Now imagine that pain intensifying, with sharp, relentless cramps gripping your abdomen. Nothing helps. As the hours pass, you’re losing fluids rapidly, from both ends, and dehydration sets in. Your body begins to spasm uncontrollably, your skin turns cold and bluish, and your eyes sink into your face. By evening, the severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance cause your organs to fail, sending your body into shock. For those hit with cholera, what probably began as a normal day could end in their death before the day was even over.

Cholera had been lurking in human history long before it reached the streets of London. The disease’s origins trace back to the Indian subcontinent, where descriptions of symptoms like those we just talked about can be found as far back as the 5th century BC. But it wasn’t until the 19th century that cholera went global, thanks to expanding trade routes and colonialism.

The first cholera pandemic began in 1817, sweeping across Southeast Asia before spreading to the Middle East, Africa, Europe, and the Americas. The word “cholera” actually comes from the Greek word kholera, which means “bile” or “sickness from bile.” People had been using it for centuries to describe nasty stomach illnesses long before they knew what actually caused it.

By 1854, London had already endured multiple cholera outbreaks, and at this point, the city’s residents knew the drill. They had science on their side. Clearly, it was just some super-bad miasma. You know, miasma–“bad air” that comes from decaying or foul-smelling substances.

The city’s poor sanitation meant foul smells were a constant, but after the hottest summer months, the colder weather of autumn and winter often made the air seem less noxious. Since cholera outbreaks often coincided with summer, they assumed that once the cooler weather set in, the threat had passed. Without scientific understanding, they saw cholera as something that “blew in” and “blew out” with the changing seasons.

On a larger scale, there were some public works efforts aimed at tackling the filth problem. The city started rudimentary sanitation projects—clearing away refuse and waste, especially in the poorer neighborhoods. But these efforts were painfully slow. After all, no one had ever tried to clean up a city this size before. And with waste still pouring into the Thames and drinking water from local pumps being contaminated, these actions didn’t address the real issue—polluted water.

However, not everyone was convinced by the miasma theory. Enter the incredibly observant John Snow—and no, not the guy from Game of Thrones, but still, cool name, right? Born in 1813 to a working-class family in York, John worked his way up and, by 1838, had become a physician. He started out in surgery and general medicine, setting up his practice right in Soho. It didn’t take long for him to make a name for himself in anesthesiology. In fact, he was one of the first to use ether and chloroform as anesthetics, even administering chloroform to Queen Victoria during the births of two of her children. Pretty amazing, right?

John’s work as a physician brought him to ground zero of the cholera outbreaks. He was in the community, treating patients, and saw firsthand how miasma was not able to account for the way cholera was spreading in the population. He noticed that cholera hit certain groups harder—even in the same neighborhood, and missed other groups entirely. If it was all about the air, everyone should’ve been sick, but that wasn’t happening.

During the 1848 outbreak, John noticed a pattern: people who got their water from certain sources were getting cholera, while others weren’t. That got him thinking: maybe it’s the water, not the air. Snow was all about the evidence, and he cared because he wanted to save lives. A science and data nerd after my own heart. John wasn’t content to just go along with the miasma crowd. He knew figuring this out could stop the spread, and that’s why he dug deeper into the waterborne theory. But he had to wait for another cholera outbreak to occur to test his theory.

But, John wasn’t the only one making these observations in the community. Reverend Henry Whitehead, born in 1828 in Kent, England, was a curate in the Soho area, specifically serving at St. Luke’s Church in Berwick Street, Soho. His role as a curate meant he was regularly visiting the sick, comforting families, and attending to the daily spiritual needs of his parishioners. He was deeply invested in the cholera outbreak because it hit his community hard—his parishioners were the ones getting sick and dying, so it was personal. Although he did believe in miasma, based on his own observations he felt a responsibility to really figure out what was going on to protect his community.

In a tiny apartment at 40 Broad Street lived Sarah and Thomas Lewis. Thomas worked as a police constable, while Sarah managed the household and cared for their three children—a 16-year-old, an 11-year-old, and their newest addition, baby Frances. At just five months old, you can’t help but wonder if little Frances had started rolling over on her own, or babbling to the family, hitting those important milestones for little ones.

But unfortunately, Frances had recently fallen ill with a severe bout of diarrhea. Reverend Whitehead, deeply committed to his parishioners’ well-being, visited the family on August 24 to offer comfort and spiritual support.

Sarah was probably worried; diarrhea can be especially dangerous to infants. She may have mentioned to Whitehead that Frances’s cloth diapers contained a strange stool. Although the doctor had already been by and concluded the baby didn’t have cholera, there wasn’t much else that could be done. Whitehead likely offered comfort to the worried mother and said a prayer before leaving to visit another parishioner.

Frances succumbed to the illness on September 2, 1854. Tragically, her death marked the beginning of a devastating cholera outbreak that swept through the neighborhood, claiming hundreds of lives in the days that followed.

When the cholera hit, Dr. John Snow saw an opportunity to test his theory that cholera was spread through contaminated water, not the air. He quickly jumped into action, going door-to-door to ask people where they got their water and whether anyone in the household had fallen ill. Using this information, he created a detailed map of Soho, plotting cholera cases with small black bars at the exact locations where people had died.

At the same time, Reverend Whitehead was also investigating the outbreak. He went door-to-door, speaking to families, gathering information, and piecing together clues—all in an effort to trace the source of the disease. This caused him to cross paths with Snow, and the two men made an unlikely team dedicated to getting to the bottom of the mystery.

At first, Whitehead didn’t think Snow was right about the water being the source of sickness—because, well, miasma, obviously. But after talking to his parishioners, he started noticing that a lot of the people who got sick had been drinking from a specific water pump. He and Snow identified the culprit as the Broad Street pump.

Within days of the outbreak’s onset, Snow and Whitehead had determined the likely cause. They noted that most cholera cases were clustered around the pump and that brewery workers who consumed beer instead of the pump’s water were largely unaffected. On September 7, 1854, Snow presented his findings to the Board of Guardians for St. James’s parish, arguing that the pump was the source of contamination and recommending that they remove its handle.

I had no idea what a ‘Board of Guardians’ was, so I had to look it up. Turns out, they oversaw local water and sanitation. Snow couldn’t just remove the handle himself—he needed their approval. After showing them his data and map, they agreed to remove it on September 8, 1854. It’s important to note that they didn’t believe Snow’s waterborne theory of cholera was right, but they were desperate enough to try it anyway.

The pump handle was removed the next day, and new cholera cases declined almost immediately.

While removing the pump handle helped curb the outbreak, the true source of the contamination wasn’t fully understood—yet. Determined to find answers, Reverend Whitehead continued his investigation and revisited Sarah Lewis, Frances’s grieving mother. Tragically, shortly after Frances’s death, her husband, Thomas Lewis, also succumbed to cholera.

During their conversation, Sarah shared critical information: she had been cleaning Frances’s soiled diapers in a basin and dumping the wastewater into the household cesspit. This cesspit, located just feet from the Broad Street pump, was poorly maintained and leaking into the groundwater that fed the pump. She also revealed that after Thomas became ill with cholera—around the time the pump handle was removed—she had washed his soiled belongings and dumped the water into the same cesspit.

If the handle hadn’t been removed when it was, the contaminated pump would have continued spreading cholera throughout the neighborhood, worsening the already devastating outbreak.

This revelation provided the final, crucial piece of evidence Snow needed to prove his waterborne theory. The contamination pathway was clear, and Snow’s map became the foundation of his argument. It wasn’t just a collection of data points; it told the chilling story of a killer lurking unseen in the heart of Soho. The map’s stark visualization of death clustering around the Broad Street pump gave it an almost spectral quality, as if it were capturing the ghostly trail of the disease itself. This eerie impression earned it the name “the Ghost Map”—a haunting yet groundbreaking tool that remains a landmark in the history of epidemiology.

Unfortunately, John Snow wouldn’t live to see the full impact of his work. The medical establishment dismissed much of his research during his lifetime, and it wasn’t until the 1860s, when London’s sewer system was redesigned, that the connection between cholera and contaminated water was widely accepted.

The 1854 outbreak didn’t just change how we understand cholera—it reshaped how we think about disease transmission altogether. It showed that solving public health crises requires not just good science, but also collaboration, community trust, and a willingness to challenge established ideas. The partnership between John Snow and Reverend Whitehead remains a testament to what’s possible when science and compassion come together.

Their work didn’t just save lives in Soho—it set a precedent for public health efforts worldwide and gave us a chilling yet invaluable tool: the Ghost Map, a reminder of how far public health has come—and how far we still have to go.

The fight against cholera in 1854 wasn’t just about disease—it was a clash of ideas. At the time, germ theory was still an emerging concept, championed by only a few forward-thinking scientists. The prevailing belief? Cholera spread through miasma—“bad air.” This theory, rooted in ancient Greek medicine, had dominated medical thought for centuries. The idea that invisible organisms in water could cause disease wasn’t just radical—it was downright unthinkable for many.

When John Snow presented his findings linking cholera to contaminated water, he faced stiff resistance. Most health officials dismissed his data, calling it circumstantial. Even the Board of Guardians, who approved removing the Broad Street pump handle, didn’t believe Snow’s theory. They acted out of desperation, not conviction.

But the resistance wasn’t purely scientific. Admitting that cholera was waterborne meant confronting an uncomfortable truth: London’s water supply was filthy, and fixing it would require an expensive overhaul. Many of the wealthier classes, who lived far from the overcrowded and unsanitary neighborhoods hardest hit by cholera, saw no reason to spend resources on the poor. This unwillingness to address systemic inequality meant the epidemic was as much a social crisis as a medical one.

The poorest residents of Soho bore the brunt of the outbreak. They lived in cramped, unsanitary conditions, relied on shared pumps and cesspits, and had little control over their environment. Meanwhile, wealthier residents, with access to safer water sources and cleaner living conditions, were largely unaffected. This disparity wasn’t incidental—it was systemic. The neglect of working-class neighborhoods perpetuated cycles of vulnerability, leaving them to shoulder the worst of public health crises.

And here’s the thing—this isn’t just history. Even today, public health inequities persist. The Flint water crisis in Michigan, where systemic neglect left predominantly Black residents without safe drinking water, is a stark reminder of how poverty and racism still dictate who suffers the most during health crises. The story of Soho in 1854 underscores a lesson we’re still learning: public health is inseparable from social justice.

The immediate aftermath of the 1854 cholera outbreak didn’t look promising for John Snow. His waterborne theory was largely dismissed, and his groundbreaking research went unacknowledged by much of the medical community. Snow passed away in 1858, just four years after the Broad Street outbreak, never fully seeing the impact of his work.

But his efforts weren’t in vain. Over time, the evidence connecting cholera to contaminated water became undeniable. In the 1860s, Joseph Bazalgette spearheaded a massive overhaul of London’s sewer system. By improving sanitation and separating drinking water from sewage, cholera outbreaks were drastically reduced. This project set a global example for urban infrastructure reform, inspiring cities around the world to invest in clean water and sanitation.

Snow’s findings also revolutionized urban planning. Clean water supplies, effective sewage systems, and better housing became essential components of city design, transforming disease-prone neighborhoods into healthier, more livable spaces. His work laid the foundation for the modern cityscape as we know it today.

Beyond city planning, Snow’s methods transformed public health. His use of data visualization, like the Ghost Map, and his reliance on case interviews became cornerstones of epidemiology. These tools have been crucial in tackling diseases from cholera to COVID-19, where mapping infections has been vital for containment efforts. His influence is also seen in the work of global organizations like the World Health Organization and UNICEF, which prioritize clean water access as a public health cornerstone.

But as much progress as we’ve made, the fight for clean water isn’t over. Millions worldwide still lack access to safe drinking water, making them vulnerable to preventable diseases like cholera, typhoid, and dysentery. Even in wealthier nations, crises like Flint reveal how systemic neglect can compromise water safety.

The legacy of John Snow and the Broad Street outbreak isn’t just a historical milestone—it’s a call to action. It reminds us that public health requires vigilance, innovation, and a commitment to equity. From the crowded streets of 19th-century London to today’s global health challenges, Snow’s work remains a guiding light for how we protect lives and build healthier futures.

And that’s the story of the 1854 cholera outbreak in Soho—how a physician with an eye for patterns and a clergyman with a heart for his community unraveled one of history’s most harrowing medical mysteries. Their collaboration not only saved lives but also revolutionized public health and urban planning, setting a precedent we still benefit from today.

But let’s not forget the broader lessons here: public health crises don’t occur in a vacuum. They reveal the fractures in our systems, exposing the deep inequalities that leave the most vulnerable at risk. From 19th-century Soho to Flint, Michigan, the fight for clean water—and the dignity it represents—continues. Public health is a shared responsibility, and stories like these inspire us to stay curious, compassionate, and committed to equity.

If you enjoyed this episode, I’d love it if you shared it with someone who loves weird, fascinating history as much as you do—or left a review on your favorite podcast app. Reviews help more people find the show, and I’d be so grateful to have your support in growing our Bygone Echoes community.

Thank you for tuning in today! Be kind, be curious, and be ready to make history.

Suggested Readings & Resources

- The Ghost Map by Steven Johnson

- Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth

- Cholera: The Biography by Christopher Hamlin

- The Sanitary City: Urban Infrastructure in America from Colonial Times to the Present by Martin V. Melosi

For digital resources, check out our website at www.bygoneechoes.website