Madness, Carousel Rides, and the Quest for Sanity: A 19th-Century Mental Health Odyssey

Activist and Reformer Doretha Dix

Activist and Reformer Doretha Dix Source

A Patient Being Transported

A Patient Being Transported Source

Boarding the Ferry to Blackwell Island

Boarding the Ferry to Blackwell IslandSource

View of Blackwell's Asylum (1)

View of Blackwell's Asylum (1)Source

View of Blackwell's Asylum (2)

View of Blackwell's Asylum (2)Source

Heading to the Asylum from the Ferry Landing

Heading to the Asylum from the Ferry Landing Source

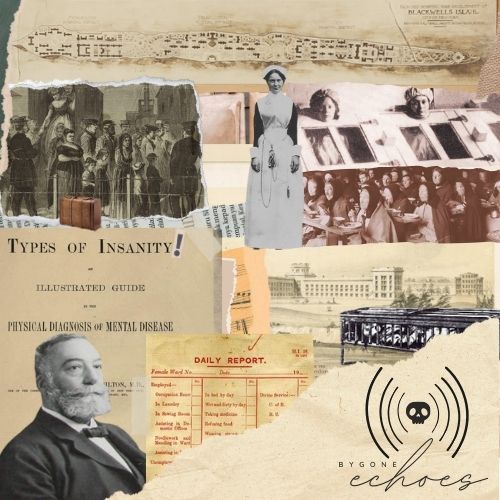

Birdseye View of the Original Blackwell Asylum Design

Birdseye View of the Original Blackwell Asylum Design Source

Blackwell Asylum's Octagon (rebranded as Metropolitan Hospital)

Blackwell Asylum's Octagon (rebranded as Metropolitan Hospital) Source

Mealtime at Blackwell's Asylum

Mealtime at Blackwell's Asylum Source

Blackwell's Asylum Crowded Conditions

Blackwell's Asylum Crowded Conditions Source

Hello, history buffs, curious cats, and everyone who accidentally hit play but is now intrigued by the promise of a journey back in time! You’re listening to Bygone Echoes, a history podcast. I’m your host, Courtney, and today, we’re talking about a topic that’s close to my heart and mind—literally, the mind. Mental health, to be exact, in the 19th century United States. But first, let’s set the stage on a global scale.

Picture this: It’s the 1800s, a century teeming with revolutions, innovations, and, not to forget, interesting fashion choices. But amidst the corsets, big gowns and top hats, there’s a silent struggle happening—the understanding and treatment of mental illness. Now, to get why this is such a big deal, we need to hop around the globe a bit.

In Europe, our friends are just beginning to shake off the cobwebs of medieval thoughts. They’re starting to think, “Hey, maybe those suffering from mental illness aren’t possessed by demons or cursed by witches.” Groundbreaking, right? The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw a shift. Places like England and France are dabbling in what they call “moral treatment”—kindness, compassion, and the radical idea that maybe, just maybe, people with mental health issues deserve dignity.

Now, over in Africa and Asia, where the plot thickens. Many communities here have long integrated mental health into their understanding of medical and spiritual well-being. Traditional healers, herbal remedies, and community support play starring roles. It’s not perfect, but there’s a sense of belonging and care that’s often missing in our Western narrative.

And then there’s the United States, a young country with big dreams and even bigger contradictions. As the 19th century rolls in, America is a patchwork quilt of ideas about mental health. Some folks are kept at home and cared for by family in varying degrees of love and misunderstanding. Others? Not so lucky.

They might find themselves in almshouses, charitable housing provided to support the most vulnerable members of the community, such as the elderly or the poor who were unable to support themselves. Almshouses were frequently overcrowded, filthy, and not at all equipped to care for those dealing with mental illnesses. Any guest who was deemed “difficult” was abused, either by their peers in the almshouse, flogged by the staff, or worse. Another option was being sent to prison—without so much as a diagnosis, let alone treatment.

It’s a world where understanding is murky, and treatment is as varied. But don’t fret, friends, because change is on the horizon. Reformers are waking up, smelling the coffee, and realizing it’s way past time for a new brew.

So, buckle up, because we’re about to dive deep into the nitty-gritty of mental health care in the 19th century—where the idea of “moral treatment” is about to take center stage, asylums are on the rise, and reformers are gearing up for a fight that promises to be anything but boring. As our story unfolds, especially in a place you might not expect—Blackwell’s Island. It’s going to be a bumpy, enlightening, and possibly even inspiring ride. Because, let’s face it, history isn’t just about the past; it’s about understanding how we got to now and where we might be heading next. And trust me, you don’t want to miss this.

In the 1800s, the world was on the cusp of a mental health revolution, or at least, the very beginning of what could charitably be called an understanding. In the United States, things are starting to get…interesting.

America, land of the free, home of the brave, and unfortunately, a place where understanding mental health was about as clear as mud. But! The winds of change were blowing, and they brought with them some key developments that would shape the future of mental health care.

First up, moral treatment! This was the radical idea that people with mental illnesses deserved kindness, compassion, and a chance at recovery in a supportive environment. Imagine that! It was like someone finally turned on the light in a dark room and said, “Hey, maybe we should treat these people like, you know, people.”

Enter the asylum—no, not the kind you see in horror movies. These were institutions built with the best of intentions, a place for the so-called “moral treatment” to take place. Large, imposing buildings surrounded by nature, where patients could theoretically live in peace and tranquility. The keyword here is “theoretically.”

But what’s a development without its champions? Enter Dorothea Dix, a name you’ll want to embroider on your heart. This woman was a force of nature, advocating for the humane treatment of those dealing with mental illness, and convincing the U.S. government to fund the building of 32 state psychiatric hospitals. Talk about a superhero without a cape! She began her career as a teacher, but shifted focus after witnessing the dire conditions of the mentally ill in jails and almshouses. Fun fact, she also served as the Superintendent of Army Nurses during the Civil War. Fun, funner fact–she was not a nurse, she just handled the administrative portion of the work.

Now, let’s talk about the people who worked in these asylums. First and foremost, our nurses. Nurses, often women, were on the front lines, their roles shaped by societal views on gender and class. Education? Not exactly the priority. Compassion? Hopefully. Abuse of power? Unfortunately, more common than we’d like to admit. However many nurses took their roles to heart, providing care and compassion to their charges as best they could.

Doctors weren’t much better off. The criteria? Be male, be white, and have a degree that suggested you knew something about medicine. Actual medical experience, not required. Actual understanding of mental health? Completely optional. This was an era when medical practice was as much art as science, and sometimes the art was more like finger painting.

And then, there’s Thomas Kirkbride. Architect, doctor, visionary. He had a plan, literally—the Kirkbride Plan. Kirkbride believed in creating buildings designed to heal through their very structure, with long, rambling wings and lots of natural light. If architecture could cure, Kirkbride’s buildings were the prescription.

So who were these treatments for? Back then, the term was “lunatics” and, well, it’s complicated. There were legitimate mental health challenges, some that we’d recognize today—like depression or schizophrenia, or if you were suicidal. Sometimes, if you were afflicted with certain conditions, like epilepsy, you were sent to an asylum.

“Monomania” was a popular diagnosis by medical professionals at the time, and was an early attempt by the medical community to begin understanding and categorize what they were observing. Those suffering from “monomania” were described as having an exaggerated or obsessive enthusiasm for a single subject or idea. For example, you could be diagnosed with “religious monomania”, a condition where an individual displays extreme religious fervor, to the point where it significantly interferes with their daily functioning or leads them to exhibit behaviors that society deems abnormal or inappropriate.

Society and cultural norms played a huge part in deciding who was or was not mentally ill. People who did not socially conform or were “socially inconvenient” were often committed. You could be sent to an asylum for things like being overly chatty, promiscuous, homosexual or just simply being down on your luck. Mental illness, it turned out, was often in the eye of the beholder.

And then, the Civil War happened. A time of unimaginable trauma that would forever change the landscape of mental health care in the United States. Soldiers returned home suffering from “Soldiers Heart”, what we’d now call PTSD. Suddenly there was an increased need for care, compassion, and an understanding in a society ill-prepared to provide mental health care.

Many institutions were built or expanded to help meet the growing need. If you had money, you could end up at a place like McLean Hospital in Massachusetts. It was a pioneer in mental health care and understanding, and patients have included celebrities and famous figures. Patients were treated with kindness and compassion, although the institute itself has had its fair share of challenges. Or, you could end up at a place like Willard Asylum in New York. In the late 1800s, Willard was the largest institution of its kind and served around 50,000 patients in its lifetime. While they granted patients a great deal of freedom, almost half of their patient population died within its walls and it’s clear that many patients realized after being admitted they would not leave the hospital alive.

Our focus today will be on the infamous Blackwell’s Island. Blackwell’s Island was a place that embodied all the hope, despair, and sheer human grit of the era.

Picture it: New York City, bustling, expanding, and in dire need of facilities for its less fortunate. Enter Blackwell’s Island, the city’s answer to a growing problem. The City of New York purchased the island in 1828 from the Blackwell family, with the vision of using it for charitable and correctional purposes.

The asylum was originally envisioned as a beacon of hope, a place where moral treatment wasn’t just an idea but a practice. The goal? To help, not to hide; to cure, not to confine. The New York City Lunatic Asylum, which I’ll be calling the Asylum on Blackwell’s Island, was New York’s first publicly funded mental hospital and the first municipal mental hospital in the United States.

Blackwell’s Island is a sliver of land in New York’s East River. It lies between Manhattan Island to the west and the borough of Queens on Long Island to the east. The island is approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) long and 800 feet (240 m) across at its widest point. Historically, it was significantly smaller, but landfill projects have altered its size and shape over time.

In the 19th century, access to the island was by ferry, a journey across the waters that separated the institutionalized from the bustling life of New York City. Once you arrived, getting around was a walk through a landscape filled with contradiction—beauty on the surface, despair beneath.

The island itself was a hub of activity. Hospitals, a prison, an almshouse, a workhouse, chapels, workshops—like a small city dedicated to the outcasts of society. They did not have a dedicated fire service, so in case of a fire the firetruck and firemen had to be ferried to the island.

The architecture? Not exactly Kirkbride’s Plan, but it had its charms. Long buildings, sprawling grounds. The buildings were designed with functionality in mind. Many of the buildings were designed in architectural styles that were popular in the 19th century, such as Gothic Revival and Romanesque Revival. These styles were chosen for their imposing appearance, which lent the institutions a sense of authority.

The asylum was a grand design by the one and only Alexander Jackson Davis. Picture this: a central octagonal tower that sounds more like a feature from a fairy tale castle than a hospital, meant to link two sprawling wings for male and female patients. It’s ambitious, it’s visionary, it’s… well, only partially realized.

Thanks to the ever-present specter of budget constraints—because what historical tale would be complete without them?—the grand vision got a bit of a trim. What we ended up with were two wings clinging to our central octagon, housing the heart and soul of the asylum: patient rooms and those crucial administrative areas.

From the moment its doors swung open in 1839, the asylum was overwhelmed, a victim of its own necessity. Designed to be a sanctuary, it became a symbol of the era’s struggles with mental health, understaffing, overcrowding, and underfunding. To deal with the explosive need, those in charge built awkward wooden structures to house asylum patients. It was like a mini-village of mismatched aspirations and architectural afterthoughts. Initially, men and women were patients of the asylum.

Patients were separated in the asylum. The primary distinctions were made based on gender, the severity of the patients’ conditions and whether they were violent, and their ability to work or participate in asylum activities. Patients that were able to work were put to work around the asylum, tasked with cleaning, laundry and other duties around the institution.

By the dawn of 1871, a game of musical chairs began, with male inmates being whisked away to Ward’s Island in a bid to, you know, actually move without bumping elbows. This shuffle aimed to ease the sardine-can conditions, but let’s be honest, the word ‘severe’ still doesn’t quite capture the essence of life within its walls.

Remember, Blackwell’s was supposed to house the mentally ill under the guiding principles of moral treatment. The intention? Good. The execution? Disastrous. Overcrowding became the norm. The care tailored? Hardly. The environment therapeutic? Only in the most optimistic of brochures.

It’s here, on this island, that the stories of thousands unfold—stories of suffering and neglect, but also of resilience and, sometimes, redemption. The staff, undertrained and overworked, struggled against a tide of impossibility. The patients, caught in a system that oscillated between neglect and abuse, sought comfort in the few rays of hope that pierced their shadowed world. It’s through their stories that we learn, grow, and strive to create a future where mental health is not a stigma but a shared human experience, deserving of compassion, care, and dignity.

Diving into the heart of Blackwell’s Island, where the walls, if they could talk, would tell a thousand stories of sorrow, hope, and the resilience of the human spirit. What was life truly like for the patients at this institution? Buckle up; it’s going to be an emotional ride.

Your journey starts, not with a grand entrance, but with the rattlin’, bone-shakin’ journey of a police wagon trundlin’ its way down what the locals call “Misery Lane.” That’d be East 26th Street, nestled ‘twixt the chill grasp of First Avenue and the murky waters of the East River. Your final stop? The ominously named Charities Pier, right where East 26th plants a kiss on the river’s edge. You step off the wagon, marking a reluctant pause to a voyage you never dreamt of adding to your list of must-dos. The air’s thick with the clamor of human feelings—weepin’, shoutin’, the endless drone of the crowd. It’s a whirlwind for the senses, with the strong stench of horse manure, city filth, and a faint, eerie whiff of decay hangin’ about. Round you, some faces are marked with tears, while others are twisted in shouts.

This spot’s a meeting place for New York’s most varied collection of souls—each one there, a livin’, breathin’ patchwork of the city’s stories. The atmosphere’s charged with a blend of hope and surrender as a mixed crowd waits: the penniless brushin’ elbows with the beaten down, the uneasy mixin’ with the outlaws, and among them, those lost in thoughts most can’t even begin to understand.

Then, like the turn of a page in a play, the ferry pulls in. Finally. It’s not just any boat; it’s the vital link ‘tween the hustle and bustle of New York streets and the island known equally for sanctuary and imprisonment. On board, a peculiar mix of folks mingles with the mundane—patients, inmates, those sworn to care for them, beasts that’ll likely never feel farm grass underfoot again, and the essentials to keep an island of establishments goin’. Together, they cross the East River, its surface a mirror to the quiet before the storm of their new beginnings. And for many, this trip was one without return—they’d never leave the island again.

Steppin’ off the ferry, all are funneled through the cogs of an administrative beast aimed at sortin’ and assignin’—a process that strips away names, replacin’ them with numbers and diagnoses, ward placements, and roles within the island’s intricate web. It’s here, at this juncture, that the next chapter of their tales unfolds.

And just like that, ye find yerself in the processin’ line, where the welcome mat is more akin to a quick look-see. Here, a couple of pointed questions—or sometimes just a sharp look—is all it takes for them to brand ye. Diagnosis by simple gander, how… efficient? The doctors, nurses, and assorted staff are either too pressed for time, or let’s be frank, not exactly keen to dig into your life’s story. So much for that warm, comforting notion of moral treatment we’ve been spun tales about.

Now, it’s supper time, and you, along with the other fresh faces of the asylum, are herded to the dining hall. What’s on the menu? Moldy bread that’s takin’ a turn at bein’ an experiment, a dubious stew pretendin’ to be soup, and a swill bold enough to call itself tea. If this is their version of high cuisine, your hunger has suddenly vanished. But not to worry, your newfound lack of appetite goes unnoticed by the staff.

Supper’s over, and it’s time to get ready for bed, which in asylum speak means it’s time for a communal bath that feels more akin to a ritual from the dark ages. Stripped of your garments and what little dignity you’ve got left, you’re scrubbed down by fellow inmates under the sharp eye of a nurse. And oh, aren’t ye the lucky one, you’re not first in line. After the one with the open sores and another with a cough that could star in its own tale of horror, it’s finally your turn. The water’s turned from barely warm to a frigid sludge, and they scrub you down with the vigor of a scullery maid tasked with cleanin’ the week’s pots, leavin’ your skin to question its lot in life. The final indignity? A towel. Yes, a single towel, shared amongst all, because why waste a perfectly good towel on just one soul?

As the sun dips below the horizon, ye find yerself locked in what they kindly call a single-person cell—I mean, room—by the nurses for the night. Ye’re left in the dark, with nothin’ but a thin, scratchy blanket for warmth. There’s a straw mattress on the floor, doin’ double duty as both your bed and chair. Likely, ye’re sharin’ this cozy spot with at least three others, their minds mayhap touched or not by madness. The night, long and unforgiving, offers scant comfort from the day’s trials. Good luck catchin’ any shut-eye.

If the stench of the communal chamber pot hasn’t roused ye, then the biting cold surely has—given the time’s belief that the chill had no bearing on the mental state. When your cell is sprung open, you and your mates are herded to the communal wash facilities, a sight far removed from cleanliness. Picture a trough setup, seldom scrubbed, a haven for sickness and despair. Breakfast is but a repeat of the prior evening’s nightmare, maybe this time ye attempt to stomach it despite your disgust.

Once breakfast is done, you’re led to the sitting area. Long wooden benches scatter the space. And there ye sit, stiff-backed and silent, for hours on end, save for when ye’re pulled away for cleaning or some other drudgery. Patients were made to sit, upright, on these unyielding benches for endless hours. No shifting, no moving; should ye dare to try and find a bit of comfort, the nurses or attendants would sternly correct your posture. No reading, no games, no chatter during these hours. Ye just sat there.

But now and then, a glimmer of joy would cut through the gloom on Blackwell’s Island. On those scarce sunny days, patients were allowed a spin on the carousel, a fleeting reprieve on painted horses from the shadowed routine of their days. And then there was the dancing—the “Annual Lunatic’s Ball” stood out as a moment of light, where patients could step, twirl, and for a brief time, shed their burdens beneath a blanket of music and temporary liberty.

But you’re here for treatment, aren’t ye? To be cured of what ails ye. “Treatment” is a term they toss around loosely here. Theories on how to mend ranged from the gentle—like fresh air and solitude—to the downright cruel. Bloodlettin’, hydrotherapy, and sensory deprivation were all too common, often leavin’ folks worse off than they started. Despite all the talk of “moral treatment,” which advised against restrainin’ the patients, restraints were used. These included garments much like straight-jackets, wrist ties, or bein’ put in “Utica cribs”—long, narrow boxes with slats for sides, and tops, sometimes even the bottom, makin’ it impossible to sit up or get out.

There were moments, though, when treatment felt genuinely therapeutic. Music, that eternal comfort, would weave its way through the halls, lifting spirits or calming troubled minds. Then there were the walks along the island’s paths, breathin’ in the fresh air, a bit of solace from the oppressive wards. This was physical activity at its most gentle, a nudge of normalcy in their twisted routine. So, amidst the dubious soups and shared baths, there were these bits—small, but mighty—where treatment felt almost… healing.

Crossin’ paths with a doctor here was a rare thing, and more often than not, it was more trouble than it was worth. The doctors, they’d dismiss us patients right out, never botherin’ to dig a bit deeper into who we were or what might be tormentin’ our minds. Plenty of these doctors were just wet behind the ears, usin’ their stint on this island as a chance to try out their theories and get a bit of practice, all because there wasn’t much keepin’ an eye on them or makin’ them answer for their doings. Would ye believe it, it wasn’t until the 1870s that the law started to tighten up, insistin’ on a bit of proper training. Finally, to be a doctor at this asylum, ye then needed a real medical degree and a few years of actual medical work under your belt—mad, isn’t it? Once a doctor got enough know-how in dealin’ with the likes of us, they’d typically be off as quick as they could, chasing after jobs that lined their pockets a bit better.

Nurses, they were a mix of saints and sinners, if ever there was one. Some poured their hearts into carin’ for us, truly believin’ in the work they did. They had a real drive to look after us, to make a difference. But then, there were those who were just biding their time, happy for the roof over their heads and a bit of stability. And others? They wielded their power like a club, with mistreatment and neglect as common as the mornin’ mist. Abuse, it varied from layin’ hands on the patients, to outright bullyin’, to puttin’ us through treatments that were more akin to torture. If you ever thought to complain to the doctors, it fell on deaf ears. The nurse’s word was law, and that was that.

Most days, we were under the care of these nurses, but with not enough hands to go around, they brought in help. And by help, I mean inmates from the nearby prison on the island, pulled in to act as attendants ’round the hospital. As Dr. Thomas Kirkbride put it, we were “abandoned to the tender mercies of thieves and prostitutes.” And let me tell you, it went about as well as you’d imagine.

It’s a grim truth, one that’s hard for us now to fully grasp. The day-to-day existence of a patient on Blackwell’s Island was filled with hardship, a true testament to the strength of those who lived through it, and a clear reminder of the darker chapters in our history of caring for the mentally ill.

Yet, even in the deepest darkness, there were flickers of hope—tales of endurance, instances of compassion, proof of the indomitable spirit that refuses to be extinguished. As we look back on these stories, let’s hold onto the value of empathy, the power of understanding, and the continuous strive towards a world filled with more kindness.

Despite the island’s noble aspirations and the sometimes-genuine help it aimed to provide, it was a hotbed of controversies.

First on our list? Funding—or, more accurately, the lack thereof. Blackwell’s Island was a dream that was starved from the start, its noble ambitions choked by a constant shortage of resources. Imagine trying to bake a cake, but you’ve only got flour and water. That was Blackwell’s, trying to make something out of almost nothing.

Then there was the staffing. As we discussed, it was a recipe for disaster, with patients often paying the price. In one instance, one nurse was assigned to a 3-floor building that was full of patients. What kind of care would you expect patients to receive when staffing was so dire?

And let’s not forget about the patients themselves, a diverse group united by their suffering. Women, immigrants, the poor, the LGBTQ+community—Blackwell’s did not discriminate in its neglect. Women could be committed by a husband’s word alone, and could only be discharged from the island to a male relative. There are even stories of husbands committing their perfectly sane wives for some trivial reason or another, just to be rid of her.

Immigrants encountered a wave of hostility and bias that could be overwhelming. In an era where not speaking English could bizarrely be your ticket to an asylum, the air was thick with anti-immigrant sentiments, particularly against the Irish. It wasn’t just about not fitting in; some doctors took it upon themselves to diagnose individuals based on sweeping stereotypes, seeing through a lens clouded by prejudice rather than medical insight.

Then, you had the poor. In the shadowed corners of Blackwell’s Island, the trauma of poverty wasn’t just a backdrop; it was a pervasive, crushing force. For many, being poor was more than a state of financial destitution—it was a one-way ticket to institutionalization. In an era where social safety nets were more theoretical than practical, poverty became synonymous with mental illness in the eyes of society and its gatekeepers.

At Blackwell’s Island, being gay or lesbian often meant facing harsher realities within an already grim system. Misunderstood and marginalized, LGBTQ+ individuals endured additional layers of stigma and isolation, their identities further complicating their already challenging circumstances in an era of profound ignorance and intolerance.

Controversy swirled around the treatment methods as well. Restraints, isolation, even the architecture itself—it was all supposed to help, but often, it just made things worse. Stories of abuse, neglect, and inhumane conditions leaked out, painting a picture of a place where healing was the exception, not the rule. For many, it became painfully evident that life in the asylum not only worsened their existing conditions but also sparked new mental health challenges, a grim testament to the institution’s impact.

Sanitation, or the lack thereof, was another grim chapter in the tale of Blackwell’s Island. Disease ran rampant, unchecked and unchallenged, a silent predator among the already suffering. Typhoid, tuberculosis, dysentery—the names alone are enough to send shivers down your spine. This impacted not only the patients but the staff as well, as no one yet fully understood or embraced something as simple as handwashing.

And through it all, the public perception. To have a family member at Blackwell’s was a mark of shame, a stain on the family name that could not be washed out. It was a place of last resort, a dumping ground for society’s unwanted.

Yet, hope flickered through the darkness. In 1887, Nellie Bly’s daring undercover mission within the asylum walls at Blackwell’s Island unveiled the harrowing conditions, igniting a firestorm of reform and outrage. Even as a “sane” individual, she attested that the asylum’s dire environment could unravel anyone’s sanity. Her bravery underscores the might of investigative journalism and advocacy, proving how a single voice can challenge the status quo and catalyze change.

In 1894, the curtain fell on Blackwell’s Island Lunatic Asylum, and its cast of patients took their final bow, moving to new stages, especially Ward Island, thanks to Ellis Island opening up immigration’s latest act. The old asylum got a makeover and rebranded as the Metropolitan Hospital, tackling tuberculosis until 1955. After its final scene, the building was forgotten, left to crumble, except for the resilient Octagon, which now shines in its second act as an apartment complex, open for tours and filled with stories.

The island’s transformation—from a symbol of isolation and suffering to what is now known as Roosevelt Island, a vibrant residential community—mirrors the journey we, as a society, are on towards a more inclusive and empathetic understanding of mental health.

Blackwell’s Island and its 19th-century counterparts were key players in the evolution of mental health care, shifting from scattered, community care to a more organized, professional approach. Yet, they often missed their mark, grappling with overcrowding, underfunding, and insufficiently trained staff, which spotlighted the urgent need for humane treatment and sparked a movement for reform. These institutions laid the groundwork for 20th-century mental health advancements, advocating for patient rights and setting the stage for community care and a kinder approach to mental health. Essentially, they were a mixed bag—highlighting both the perils of past practices and the potential for progress.

As we look back on the history of Blackwell’s Island, let’s commit to learning from its lessons. Let’s strive for a future where mental health is not a cause for shame or stigma but a part of our shared human experience, deserving of empathy, respect, and care.

As we close the book on our exploration of Blackwell’s Island, it’s time to reflect on the journey we’ve taken together. From its early days as a beacon of hope to its struggles with overcrowding, neglect, and controversy, Blackwell’s Island serves as a powerful reminder of where we’ve been—and where we still need to go—in mental health care and social justice. It reminds us that history is not just a series of events but a mosaic of human experiences, each piece informing our understanding of the past and guiding our actions in the present.

Blackwell’s Island teaches us that progress is possible, but it’s a path we must walk together, armed with the lessons of the past and a vision for a better tomorrow. It’s a reminder that in the quest for a more just and compassionate world, we all have a part to play.

Let this journey inspire us to advocate for a future where mental health is prioritized, where stigma is eradicated, and where every individual, regardless of their circumstances, is treated with the empathy and respect they deserve.

Until next time, Be kind, be curious, and be ready to make history.

Interested in learning more? We recommend:

- Damnation Island: Poor, Sick, Mad, and Criminal in 19th-Century New York by Stacy Horn

- Ten Days in a Mad-House by Nellie Bly

- The Lives They Left Behind: Suitcases from a State Hospital Attic by Darby Penney and Peter Stastny

- Gracefully Insane: Life and Death Inside America’s Premier Mental Hospital by Alex Beam

The St Joseph Museums Youtube Channel has a variety of videos related to the State Lunatic Asylum #2 in St. Joseph, Missouri.

And visit our website at bygoneechoes.website for more content, episodes and photos.