Witchy Woman Woes: The Curious Case of Alice Young

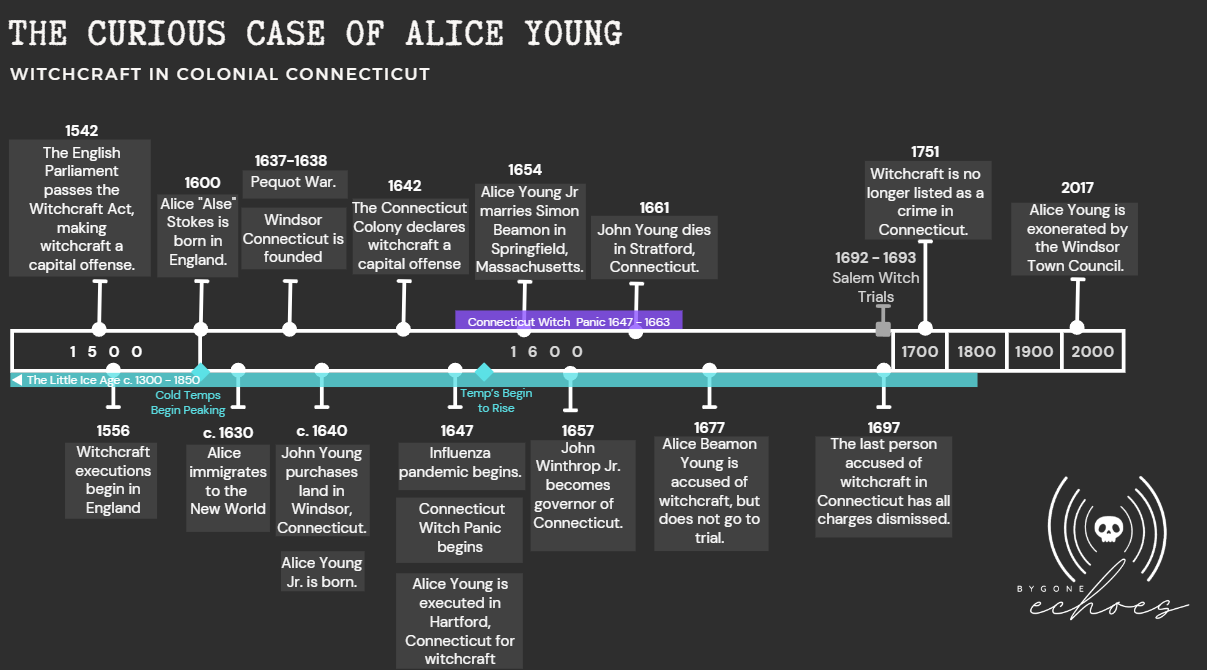

TL;DR: Alice Young, first to be yeeted for witchcraft in the American colonies, way before the Salem craze. In 1640s Connecticut, Puritans were super into the Bible, seeing the devil in every corner and confusing poor herbalists and pet owners for witches. Picture this: harsh vibes, harsher winters, and everyone’s on edge—perfect storm for a witch hunt. Alice got the short end of the stick during a flu outbreak ’cause, of course, gotta blame someone, right? Fast forward, and guess what? Connecticut chills on the witch hunts thanks to Governor John Winthrop Jr. bringing some science into the mix. Still, took until 2017 for Alice to get an official “my bad” from the town.

Transcript

Grab your broomstick friends as we travel back to the 1640s, where Puritan neck ruffs were high, superstitions were sky-high, and the stakes? Literally life or death. Welcome to Bygone Echoes, a history podcast. I’m your host, Courtney. Today, we’re stirring the cauldron of history to bring you the tale of Alice Young, the first recorded person executed for witchcraft in the American colonies almost 50 years before the Salem Witch Trials.

But first, what exactly was considered witchcraft in these turbulent times? We’ll be looking into Puritan culture, where they took the bible and everything in it literally. To Puritans, the devil was real and a literal threat to their wellbeing. Witchcraft encompassed everything from casting harmful spells—known as maleficium—to owning a suspiciously savvy pet that might be a familiar, an animal guide sent by the devil. It was a label applied to the misunderstood acts of healing, herbalism, being a person who “knew things they shouldn’t know”–like the not-so-secret-secrets of your neighbors-and unfortunate coincidences alike, such as illness, famine or as mundane as your cow has stopped producing milk or your butter suddenly spoiling.

We had witches. But, we also had the cunningfolk. These were the local healers, wise women, and men who used herbs, charms, and knowledge of the natural world to cure ailments and ward off bad luck. Sometimes respected, the common folk could tell the difference between them and a witch, sort of simplifying it to witches hurt, cunningfolk helped. But these cunningfolk resided on the edge of suspicion, and they walked a fine line; their helpful hands could quickly be deemed sinister when misfortune struck a person or a village.

Can you imagine living in a world where your neighbor’s bad mood or some unfortunate event befalling a family could lead to someone crying witch? That was Windsor, Connecticut, a city just 7 miles from the state capital of Hartford, Connecticut. And this is where Alice’s story unfolds—a tale of mystery, paranoia, and a community’s fear turned fatal.

Thank you all for tuning in. As we peel back the layers of history, remember, we’re not just talking about old, dusty books. We’re connecting the dots to see how yesterday shapes our today and tomorrow. So, grab your pointy hats and black cats, and let’s fly into the bewitching story of Alice Young.

As we set the scene in Colonial America, it’s important to grasp the world during this period. Across the oceans, monarchs reigned, innovations flourished, and cultures clashed and merged. In the 1640s, Germany was gripped by severe witch hunts, resulting in hundreds of executions during some of the most brutal purges of the era. Meanwhile, in Sweden, the peak of their witchcraft accusations culminated in the execution of 71 individuals.

In England, the legal stakes for witchcraft were as high as the gallows, with death as the grim penalty leading to sporadic trials and executions—though not quite as fervently as on the Continent. Cue the sinister rise of Matthew Hopkins, soon to be notorious as the “Witchfinder General.” His crusade of witch hunts during the 1640s cranked up the fear and suspicion to a whole new level, fueling the dark superstitions that English colonists packed in their bags and carried across the Atlantic.

These anxious settlers, primarily English Puritans, were part of a larger tide of religious and economic migrants who braved the ocean seeking both freedom and fortune in places like Hartford, Connecticut.

Hartford, Connecticut, around the 1640s, held a landscape that was as rugged as the spirits of those who sought to tame it. These settlers were a diverse group, comprising small farmers, artisans, and merchants, bound together by a stern religious ethos. The fertile land along the Connecticut River lent itself well to agriculture, offering them a chance to cultivate a new life in the New World, while the river itself served as a vital artery for trade and transportation.

The community was not just made up of Puritans but also included indentured servants, people who didn’t have the money to immigrate to the New World. Instead, these folks pledged to work for a family and, after years of toil, would receive “freedom dues” to begin their independent lives in the New World. Yet, not all were so fortunate to anticipate freedom; the darker side of this narrative witnessed the exploited labor of African slaves and Native American captives, forced into roles like domestic work, farm work, and skilled carpentry. In addition to this community, the settlers had pets—dogs, cats, and other animals—which played their part in this fledgling society, valued more for their utility than companionship.

The typical dress code was simple, sporting modest clothing made from wool or linen. The daily lives of these settlers revolved around a basic diet of locally grown vegetables, grains like corn, and meats obtained from hunting or domestic animals. Meals were often enhanced with dairy and the occasional catch of seafood from the nearby rivers.

Their homes were straightforward affairs—usually one or two-room structures made from locally sourced wood, employing timber-framing techniques to battle the elements, with gaps stuffed with mud and straw to keep out the cold. Over time, as their building techniques improved and resources became more available, their homes gradually evolved from mere shelters into more substantial dwellings.

But life in Hartford wasn’t isolated to just the local Puritans. It was deeply influenced by interactions with neighboring communities which included Native Americans, Dutch traders, and other English settlements.

Local Native American communities, especially the Pequot and Mohegan, played crucial roles in the political and economic landscape of southeastern Connecticut. Dominant in the fur trade and regional politics, the Pequot faced severe adversity in the mid-1630s when conflict erupted with the colonists. This brutal war resulted in the catastrophic decimation of the Pequot tribe, leaving deep scars on both the colonists and the area’s Native populations. Prior to this conflict, the Mohegan had separated from the Pequot and strategically allied themselves with the English, positioning themselves advantageously during the war.

After the conflict, the Mohegan rose to prominence, becoming the dominant group in the region. This shift dramatically changed the power dynamics and control of the territory, which positively impacted European trade and enhanced their security. The Connecticut River was instrumental, acting as a critical trade route that connected Hartford to the broader Atlantic markets, thereby boosting its significance in these expanded trade networks.

For our colonists, Puritan values permeated every aspect of life, dictating not only personal behavior but also the communal and legal frameworks. Governance was intertwined with religious observance, with laws that mirrored the severity of biblical commandments. These folks took the bible literally, with witches and Satan as real as sunshine. Overall, the community’s ethos was one of piety, sobriety, and an unyielding work ethic, all enforced under the watchful eyes of both divine and earthly judges.

The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, drafted in 1639, reflect this melding of communal life and religious doctrine—one of the earliest forms of written constitution in America, emphasizing a governance rooted in common consent and shared moral values.

Gender roles were rigidly defined by Puritan beliefs. Men were heads of households and held public and religious leadership roles, responsible for family and community welfare. Women managed household duties, cared for children, and were key in instilling religious values, although excluded from formal leadership. Marriage was seen as a partnership for moral and spiritual upbringing, with clear patriarchal authority. Overall, men and women had distinct, complementary roles essential to maintaining social and religious order. Widows and elderly women could hold a unique status. Widows often managed their own finances and property, gaining a level of independence and respect. Elderly women, especially if widowed, might be viewed as matriarchs, respected for their wisdom and experience. However, their status heavily depended on adhering to societal norms of piety and propriety. Those without family support faced potential hardships, relying on community assistance which wasn’t always readily available on the colonial homefront.

Amidst these structured lives, the settlers faced unexplained adversities—crops failed, livestock perished, and diseases spread, often attributed to supernatural forces due to the prevalent belief in witchcraft. This fear was legally reinforced in 1642 when Connecticut declared witchcraft a capital offense, echoing English laws and biblical scripture that commanded, “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.” The goal aimed to deter what was perceived as a genuine and dangerous threat to the community’s moral and physical welfare, but would have dire consequences.

The settlers were also in the midst of the “Little Ice Age,” a period of a few hundred years that significantly affected the climate of the northern hemisphere, including North America. This period was marked by cooler temperatures that wreaked havoc on traditional farming routines. They shifted to hardier crops like rye and barley, but these changes came with their own set of challenges. Harsher winters meant more reliance on hunting and thick, warm clothing, often secured through trade or aid from Native American allies. Homes had to be fortified against the bitter cold, adding another layer of hardship to their daily struggles.

And then there was the dark side of those hardy grains—especially rye. Prone to contamination by ergot, a toxic fungus, rye could cause ergotism, a serious condition leading to hallucinations, seizures, and even gangrene. Economically, you have to wonder if the switch from profitable maize to potentially less lucrative barley and rye could mean a dip in trade earnings, while culturally, adapting to new food staples and cooking methods could also stir up tension within the community.

All these challenges brewed a potent mix of fear and uncertainty. Strong religious convictions, intense social tensions, and paranoia spiked, particularly during times of hardship when no one could explain why illness struck unpredictably or why crops failed. The strict legal precedents from English law, combined with the isolation and fears tied to frontier life, and the precarious position of often marginalized women in society, created an atmosphere ripe for scapegoating. In this environment, it was all too easy for communities to pin their misfortunes on those viewed as outsiders or troublesome, paving the way for the tragic witchcraft accusations that would soon unfold.

Documentation of Connecticut’s witch history is slim, so piecing the story together is challenging.

In the unforgiving and rigid world of colonial Connecticut, survival was a daily challenge, and adherence to social norms was enforced with a stern hand. Alice Young, a settler in Windsor Connecticut, found herself ensnared in a web of community fears and misunderstandings. Little is known about Alice, as most records of her life have been lost to time or were not meticulously documented. What remains is a fragmented narrative pieced together by historians who have sifted through scant details to give us a glimpse of her life.

The facts we have are: (1) Alice existed. Her name is spelled in many variations, like A-L-S-E, A-C-H-S-E, and A-L-I-C-E. She immigrated to the colonies and moved to Windsor, Connecticut at some point before 1647. Alice was accused of witchcraft, convicted, and executed by hanging on May 26, 1647 in Hartford. She also had a young daughter, also named Alice Young, who was around 7 years old at the time of her execution. We also know that in 1647, a deadly influenza epidemic swept through Windsor and much of the colonies, taking many lives.

Historians have pieced together that Alice Young was possibly born in England, likely between 1600 and 1615, and her maiden name is believed to have been Stokes. The exact details of her immigration to America remain unclear, but it is probable that she arrived in the Massachusetts Colony during the 1630s and later moved to Windsor, Connecticut. At some point, she married a man named John Young, who is recorded as owning land in Windsor as early as 1640. The couple likely lived in Windsor for at least seven years before Alice’s tragic end.

By the time she faced accusations of witchcraft, Alice was a married woman, between her 30’s and 50’s, with at least one child. It is suggested that her husband, John, might have been a carpenter, as indicated by the carpentry tools listed in the estate of a John Young who died in Stratford, Connecticut, in 1661. This John sold all his Windsor holdings in 1649, possibly in a bid to leave the town that had executed his wife.

The details surrounding the accusations against Alice are murky. She may have been a healer, a cunningwoman (like we mentioned at the beginning of this episode) or midwife—roles often suspiciously viewed as linked to witchcraft. Or, maybe she “knew things she shouldn’t have known”, like someone’s secrets, and this made her a target. Alternatively, she could have been a widow or maybe her husband was sickly, and she stood to inherit property in a male-dominated society, posing a threat to the established order. Some sources hint that Alice had been accused of other minor crimes, like theft, before being charged with witchcraft.

The context of her accusation is rough, occurring during a deadly influenza epidemic that swept through Windsor in 1647. Maybe she managed not to get sick, while everyone else did? It is suggested that she lived next to a family who lost four children to the pandemic, and this may have made her an easy scapegoat for a community desperate for explanations in the face of overwhelming loss and fear.

Alice’s trial, like others of its time, would have been governed by English common law blended with Puritanical rigor. The General Court, composed entirely of men, oversaw legal proceedings that involved community testimony and biblical law, with consequences ranging from fines to the ultimate sentence—execution. Though Samuel Stone, the minister in Hartford at the time, did not participate directly in her trial, his role as a religious leader would have been significant in influencing the magistrates’ decision on whether Alice was a witch. It leaves us to wonder too, after she was accused did she confess freely? Or was her confession coerced like so many others? What sort of treatment would she have been subject to as she waited for death? Did she think of her family back in England? Did she worry that her husband and young daughter would get on without her?

On May 26, 1647, Alice Young was hanged at Meeting House Square in Hartford, the site of what is now the Old State House. She holds the grim distinction of being the first documented person executed for witchcraft in the American colonies. The scant records from her trial mention only that she was “arraigned and executed at Hartford as [for being] a witch.” Matthew Grant, the Windsor town clerk, succinctly noted in his diary, “Alse Young was hanged.”

The uncertainty of Alice’s final resting place adds a somber note to her story, with some speculating that her body was unceremonially disposed of near the gallows. Her execution set a haunting precedent for the handling of witchcraft accusations in the colonies, leading to a series of trials and executions that would scar New England’s history throughout the 17th century.

In the uncertain and ominous world of colonial New England, mysteries like crop failures, plagues, or untimely child deaths were often attributed to malevolent forces. Without the lens of modern science, black magic, and witchcraft became convenient explanations for these calamities. Throughout history, countless individuals, particularly women, have been executed on flimsy accusations of witchcraft, many dying in dire conditions while awaiting trial. The witchcraft trials often targeted women perceived as wielding too much power or those who deviated from prescribed social norms.

The primary drivers of these witchcraft convictions included deep-seated misogyny, intense community panic, and a blend of contributing factors. These included strong religious convictions, social tensions and paranoia post-Pequot War, harsh legal precedents from English law, and the isolation and fears associated with frontier life. This complex mix created a volatile environment where women, particularly those marginalized or in positions of relative power, became scapegoats for broader societal anxieties.

Historical records indicate that, in the 17th century, a total of between 37 and 43 witchcraft cases in Connecticut, 11-16 of which resulted in executions. The numbers conflict, but that’s what I’ve found.

Alice’s execution was the beginning of the Connecticut witch panic, which lasted around 20 years. This shift was significantly influenced by the return of Governor John Winthrop Jr. to Connecticut. Known for his scientific background and moderate religious views, Winthrop brought a critical and rational perspective to the handling of witch trials. His experiences with alchemy and knowledge of natural magic informed his skepticism toward the often baseless accusations of witchcraft. Under his guidance, the legal proceedings required more substantial evidence, mandating that multiple witnesses corroborate any act of witchcraft.

This prudent approach led to a significant reduction in witchcraft accusations, although witchcraft remained a capital crime until 1715. By 1670 the witch panic in Connecticut ended, and the last witchcraft trial in Connecticut was in 1697, and the charges were dismissed. The trials in Connecticut prefigured those in Salem by nearly half a century and profoundly impacted the American legal and social landscape, particularly shaping perceptions of women and the disenfranchised.

Before we close today’s episode, let’s reflect on the lasting impact of Alice Young’s story. After Alice’s execution, her family continued to feel the reverberations of her fate. Her husband left Windsor and passed away in 1661. Their daughter, who I’ll call Little Alice, made her way from Connecticut to Springfield, Massachusetts, where she married Simon Beamon in 1654. The couple raised at least 12 children in what appears to have been a relatively stable and peaceful life until Simon died in 1676. Unfortunately, upon his death, Little Alice could not escape the shadow of her mother’s tragic fate.

About 30 years after her mother was executed for witchcraft, Alice herself faced accusations of the same crime. Witchcraft. Fortunately for Alice, her son, Thomas Beamon, stepped into the legal arena in 1677 to defend his mother’s honor. He sued a man for slander who had claimed, “his mother was a witch, and he looked like one.” Fortunately, justice sided with Thomas, and he won the case, preventing the prosecution of his mother. Historians suggest that Little Alice’s family support, particularly from her sons who would have inherited her property and were well-respected in the community, played a crucial role in shielding her from the fate her mother suffered.

Despite the decline of witch trials, the stigma attached to such accusations endured, casting a long shadow over families for generations. Yet, Alice’s story shows us the power of family and legal advocacy in challenging and overcoming societal prejudices.

In a significant posthumous acknowledgment, Alse Young was formally exonerated by the Windsor Town Council in February 2017, a move spearheaded by local historian Beth Caruso. Today, Alice Young is memorialized with a brick in Windsor’s downtown park, a testament to the enduring impact of her story and a reminder of the perilous power of fear and superstition in shaping communities and legal practices.

And that wraps up our journey through the chilling saga of Alice Young, whose ordeal ignited the fuse of America’s witchcraft hysteria. From the grim gallows of colonial Hartford to the modern-day memorial in Windsor’s downtown park, Alice’s story serves as a reminder of the dangers of fear and superstition when wielded by society.

After exploring the events that led to Alice’s execution, it’s fascinating to see how these ripples from the past still touch our present views on justice, community, and the ostracization of those deemed “other.” My hope is that today’s episode sparks a flame of empathy, encourages a dash of critical thinking, and inspires the bravery to challenge the tales we’ve been told.

Thank you, everyone, for listening to Bygone Echoes. Join us next time as we unearth another forgotten story that shaped our world. Until then, be kind, be curious, and be ready to make history.

Interested in learning more? We recommend:

- Witches of America by Alex Mar

- Connecticut Witch Trials: The First Panic in the New World by Cynthia Wolfe Boynton

- Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England by John Demos

- The Devil in the Shape of A Woman by Carol F. Karlsen

You can also visit our website at bygoneechoes.website