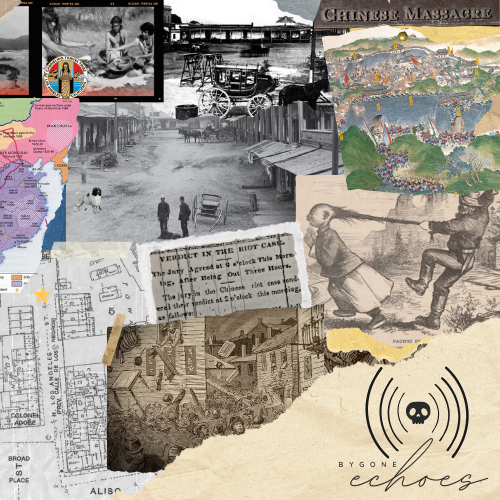

LA Gone Wild: The 1871 Chinese Massacre and America’s Forgotten Hate Crime

TLDR; In 1871, a mob of 500 in Los Angeles stormed Chinatown, lynching 19 Chinese immigrants after a white rancher, Robert Thompson, was killed while inserting himself into a tong feud (bro should’ve just sat this one out). Fueled by systemic racism and anti-Chinese propaganda, the violence left Chinatown in ruins. No one faced real consequences, thanks to California’s racist laws barring Chinese people from testifying in court (#JusticeSystemFail).

Fast forward to 2025, and it’s giving “history on repeat.” Immigrants are still scapegoated, fear-mongering policies are trending, and marginalized communities are left to fend for themselves. The vibes are not immaculate. This episode dives into why we need to break the cycle of hate, uplift immigrant voices, and stop history from becoming a never-ending sequel.

Takeaway? Don’t be the person who ignores the group project of progress. Speak up, get involved, and remember: justice is everyone’s business.

Transcription

⚠️ Trigger Warning ⚠️

Before we begin, I want to let you know that this episode covers some incredibly difficult topics: racially motivated violence, lynching, systemic racism, and discrimination against immigrants. I’ll also touch on political issues that may feel heavy or stressful, especially given what’s happening in the world today.

If these subjects feel like too much right now, it’s okay to pause and return when you’re ready. Please take care of yourself as we explore this painful but important chapter of history, because while it may be from the past, its echoes are still with us.

Thank you for being here.

Hey there, history lovers and curious minds! Welcome to Bygone Echoes, a history podcast where we uncover the good, the bad, and the downright horrifying ways humans have treated each other throughout history. I’m your host, Courtney, and I’m so glad you chose to be here.

I’m excited! Chinese Lunar New Year begins this Wednesday, and it’s a time of joy and renewal for many Chinese and other Asian communities around the world. But as I worked on this episode, it struck me how much resilience it takes to carry a sense of hope forward, even after unimaginable hardships. The Chinese community of LA in 1871—the focus of today’s story—was one such community. Despite enduring horrific violence and systemic racism, their strength and perseverance remind us that, even in the darkest moments, survival itself is an act of defiance.

For me, today’s topic is a little too relevant. I’ll admit it’s been unsettling to research. So, let me confess something before we start: This year, I actually planned out the podcast episodes in advance—yes, I’m super proud of myself, thank you for asking! The goal is one episode a month, because, well, I’ve chosen to fly solo on this podcasting journey, and doing it all on my own takes time.

I was going to wait until February to cover this, because I also try to finish atleast one book on the topic too, but I couldn’t—this story feels too urgent right now. I’m not afraid to admit it: I have big feelings about what’s going on in the place I call home–the USA, and I need to talk about this history, like, right now.

Today, we’re traveling back to Los Angeles, California, in 1871—a time when the city was still a budding community, far removed from the vibrant, world-famous cultural hub it has become today. Back then, LA was a small, rough-and-tumble frontier town with barely 6,000 residents. It was the kind of place where lawlessness was the norm, racial tensions ran high, and violence lurked around every corner. It was also the setting for one of the deadliest racially motivated massacres in U.S. history.

Picture this: a mob of 500 vigilantes storming through Chinatown, dragging Chinese immigrants out of their homes and businesses, lynching them from makeshift gallows, and leaving their bodies as a grim display of deep-seated hatred. By the end of the night, 19 Chinese immigrants were murdered. It was chaos. It was barbaric. And here’s the part that will make your blood boil: almost no one was held accountable.

And yet, I’d bet most of us never learned about the 1871 Chinese Massacre in school. It’s not in your standard American history textbook, and it’s rarely talked about in the context of the violence and racism that have shaped this country. Why? Maybe because it’s easier to forget. Or maybe because it was so poorly documented—racial violence like this wasn’t exactly remarkable back then. Or maybe because it forces us to confront some uncomfortable truths about how deeply racism and xenophobia are embedded in our history.

Now, here’s where things get even more unsettling. As I’m recording this, it’s January 2025, and we’re watching a new wave of political policies and rhetoric that sound eerily similar to the forces at play around 1871. Immigrants are once again being scapegoated. Fearmongering is in full swing, and policies like mass deportations, the end of birthright citizenship, and the reinstatement of the “Remain in Mexico” rule are being rolled out as we speak. The echoes of 1871 aren’t just faint whispers of the past—they’re loud, jarring screams.

Okay, deep breath. That’s… a lot. And trust me, this story only gets heavier. But that’s why it’s important to tell it—because even the darkest moments in history have lessons for us today.

So, what does the Chinese Massacre of 1871 teach us about America’s long history of using immigrants as scapegoats? And what does it reveal about who we are as a country today? Because, let’s be real—history isn’t just about old facts. It’s about patterns. It’s about choices. And most importantly, it’s about deciding whether we want to keep repeating the same mistakes, or break the cycle—which we’ve shown we can do, time and time again. The awesome part is, we get to choose. We all have a part to play, whether we like it or not.

Today, we’ll dig deep into this tragic chapter of U.S. history. We’ll unpack the events leading up to the massacre, explore the racist systems that made it possible, and connect it to the immigration policies shaping the United States right now. Together, we’ll ask: What does this say about who we are—and who we want to be as a society? Let’s get into it.

Let’s talk about 1871 for a second, because the world at that time was busy. I want you to keep in mind, that while the things leading up to the massacre and the massacre itself were occurring, things were on and poppin’ around the globe.

Globally, 1871 was a chaotic year—nations like Germany and Italy were unifying, and workers in France were rising up in revolution. While the transatlantic slave trade had officially ended by this time, its effects lingered in Africa. Regions had been left depopulated, economies disrupted, and communities & societies destabilized after centuries of abduction, forced labor and violence.

The Qing Empire, what we call China, was straight-up falling apart—decades of chaos, poverty, and foreign interference had left the country barely able to hold it together. Southern China, in particular, was hit the hardest, with millions of people just trying to survive after various wars, including the Opium Wars and Taiping Rebellion, and wave after wave of natural disasters.

Floods along the Yellow River destroyed farmland and displaced millions, while droughts in the south left families with nothing to eat. These disasters triggered waves of famine, forcing people to sell everything they had—or relocate, if they could.

The Taiping Rebellion was one of the deadliest conflicts in human history, claiming an estimated 20–30 million lives. It left southern China in ruins, forcing countless families to make impossible choices just to survive. The Rebellion lasted almost a quindecade—I just learned that word, by the way! That’s 15 years, in case you, like me, are not up on your obscure units of time. And we’re saying 30mil people died, right? It’s so abstract. Like, what even is 30 mil?

So, let’s break it down: Imagine the entire population of Australia wiped out. Gone. To put it another way, during the rebellion’s 14 years, nearly 4,000 people died. Every. Single. Day. And while I don’t like measuring tragedies in “9/11s,” let’s go there for a second, because it has been suggested that some folks find it easier to grasp. That’s the equivalent of a 9/11-level tragedy happening every single day for over a decade. No breaks. No weekends. No holidays. 365 days a year, 7 days a week, and don’t forget your extra day when you have a leap year. The Taiping Rebellion wasn’t just a conflict—it was a human catastrophe on a scale that’s almost impossible to comprehend.

And for a lot of people, staying in China wasn’t an option—it was life or death.

The United States, on the other hand, had the promise of something to immigrants. But, what was the USA up to around that time?

Well, friends, Reconstruction was underway, and for the first time ever, Black Americans were being granted rights! Well… the men, at least, had rights. Black men could vote, hold office, and participate in government. But, the white majority did not handle it well.

White supremacists, led by groups like the Ku Klux Klan, had a very hard time managing their feelings about sharing power or being seen as equals. Instead of sitting with their discomfort and maybe, I don’t know, rethinking their worldview—they acted out violently. Lynchings, voter intimidation, and outright terrorism became their go-to strategies as they did everything in their power to drag the country back to a time when they didn’t have to share and their status at the top went completely unchallenged.

Meanwhile, out West, white settlers weren’t behaving much better. They snatched up Indigenous lands by breaking treaties, violently displacing Indigenous peoples, and routinely committing massacres.

The recently completed Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 had supercharged westward expansion. It was now easier than ever for settlers to flood into Indigenous territories. The railroad also brought Chinese laborers to the region—the men who had worked tirelessly to build it but were now being scapegoated and excluded from the opportunities it created. For some, it was a time of promise and progress; the world was their oyster. But for others, it was loss, destruction and devastation.

Our story today takes place on the West Coast, a land of contrasts. Cities like San Francisco were booming, initially fueled by the Gold Rush and sustained by immigration and trade, while smaller towns like Los Angeles were still transitioning from sleepy pueblos to bustling urban centers.

It was a place of opportunity for some—but that opportunity was often built on the backs of marginalized groups like Chinese immigrants, Indigenous peoples, and Mexican Californians. At the same time, it was rough, lawless, and deeply unequal, with racial tensions simmering just below the surface—or, as we’ll see in this story, exploding into violence.

Once upon a time, the Los Angeles area was known as Yaanga and was the ancestral home of the Tongva, or Gabrielino, people. It covered just 28 square miles—basically a little bigger than a marathon course. Back then, the area was known for its vast, open spaces, with rolling hills, wide plains, and dry riverbeds.

The Tongva people have lived in the region for thousands of years, and a small population still resides there today. The Tongva have a spiritual connection to this area, and it is central to their identity, emphasizing respect, stewardship, and a deep understanding of the natural world’s intrinsic value. Tongvu society traditionally revolved around honoring nature, hunting, gathering, and basket weaving. I did read that they were also seafaring people, but other sources conflict, so I’m not sure exactly. Unfortunately, by the 19th century, the Tongva population had been nearly wiped out.

First, the Spanish rolled in during the late 1700s and forced the Tongva people into the mission system, where they were essentially enslaved, converted to Christianity, and stripped of their culture. Then, when Mexico took over in 1821, the missions were replaced by ranchos—huge land grants handed out to wealthy Mexican settlers. The Tongva? Still pushed aside, now working as low-paid laborers on the very lands that had belonged to them for generations.

And then, after the U.S. annexed California in 1848, white settlers swept in, snatched up the ranchos for themselves, stole even more land, and violently displaced what was left of the Tongva community. By the time Los Angeles officially became a U.S. city, the Tongva were almost entirely erased from the narrative.

In 1871, the city layout revolved around its early Spanish and Mexican roots. The center of town was the Plaza, a cluster of adobe buildings near what’s now Olvera Street, and that was about it. It included the Plaza Church (La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles), which had been built in the 1820s. Calle de los Negros, a narrow street near the plaza, had earned a reputation for being one of the city’s most lawless and violent areas—both a hub of activity and a reflection of LA’s darker side. It was full of gambling halls, saloons, and brothels. It was also where many immigrants lived, worked, and ran small businesses.

The population in 1871 sat at around 6,000 people, so it was more of a rough frontier outpost than a bustling city. It was dwarfed by larger California cities like San Francisco, which had boomed thanks to the Gold Rush. Los Angeles, meanwhile, still felt remote, tucked away in the southern part of the state and isolated from the more developed regions up north.

About 60 percent of the city was made up of white settlers, who controlled most of the land and wealth. The Mexican Californio population, once the majority, had dropped to about 20 percent, with many reduced to tenant farmers or laborers after losing their land. Indigenous peoples, including the Tongva, and African Americans each made up less than 5 percent of the population, often pushed to the edges of society or reduced to low-paid labor.

The Chinese immigrant community in LA was small—around 200 people total, which if I tried to math it is like 180 men and just 20 women and a few children. Though not exact numbers, that staggering gender imbalance wasn’t an accident.

Immigration laws, cultural expectations, and economic realities made it nearly impossible for Chinese women to immigrate. For those who did make it to the US, their lives were marked by unimaginable hardship, as they were treated as property and exploited for profit aka prostitution. Most of the men were young, in their late teens to early 30s, sent by their families to earn money and send it home.

And life in America? It wasn’t easy. These men worked brutal, backbreaking jobs that literally no one else wanted. Long hours in laundries, tending fields under the blazing sun, or working as cooks and gardeners for white families—this was their day-to-day. And the pay? $2 a week, thats like $50 today. Weekly, not daily. White workers could earn up to triple that amount. But compared to life back in China—where famine meant no wages—those meager earnings were worth it. Every penny sent home could keep a family fed.

They wore traditional Chinese clothing and the queue hairstyle mandated by the Qing Dynasty—a long braid that became an easy target for ridicule and even physical attacks. Their appearance was weaponized against them, making them more visible as ‘the other.’

But for all the hardships they faced, Chinese immigrants built tight-knit communities to survive. Most of them lived near Calle de los Negros, a crowded area near the Plaza that would eventually evolve into Chinatown.

The community was structured around kinship networks, regional ties from back home, and benevolent associations, which helped immigrants with everything from finding housing to paying funeral expenses. At the top of the community were merchants and shopkeepers—men who had a little financial stability and owned small businesses. At the bottom were laborers, crammed into overcrowded housing and barely scraping by.

You also had figures like Dr. Gene Tong, a man in his 30s who was a highly respected herbalist and a Chinese community leader in LA. He was beloved by his patients, both white and Chinese. He and his wife, Chang Wan, lived together in an apartment with their pet poodle. They also took in a tenant, which I see as helping their community grow.

But, like any community under pressure, tensions existed within. Many Chinese immigrants organized themselves into groups based on kinship or regional ties from their homeland, leading to the formation of ‘tongs.’ The word ‘tong,’ derived from Cantonese, means ‘meeting hall’ or ‘hall of gathering.’ These organizations initially served as social support networks, helping immigrants navigate life in a foreign land. However, some tongs evolved into criminal enterprises involved in drug trafficking, prostitution, gambling, and even slavery. Rivalries quickly formed in Los Angeles as these groups clashed over control of gambling operations, territory, and money. These disputes often escalated from verbal arguments to bloody confrontations.

But overall, it was a good thing the community had those internal structures because white Los Angeles was anything but welcoming. White settlers blamed Chinese workers for “stealing jobs,” even though Chinese immigrants were often doing work that white laborers didn’t want. Sound familiar? Newspapers ran racist editorials portraying Chinese people as dirty, immoral, or inherently criminal. And physical harassment was almost a daily occurrence.

White children would spit on Chinese workers, throw rocks, or kick them in the street. Adults were no better—pushing them off sidewalks, shouting slurs, and mocking their clothing and hairstyles. And that’s just the small stuff. Larger acts of violence—mob attacks, lynchings—were all too common.

Remember, this is 1871 Los Angeles we’re talking about, a city already infamous for its lawlessness and high murder rate. The anti-Chinese sentiment simmering in this city wasn’t new. It had been building for years, stoked by economic fears, racist propaganda, and the belief that Chinese people didn’t “belong.”

It was in this highly volatile environment that two rival tongs—the Hong Chow Company and the Ning Yung Company—came to blows.

Before we discuss the incident itself, quick disclaimer. The sources I used varied on the specifics at times, omitted details and conflicted eachother, so keep in mind below is not the gospel truth. Thanks!

In October 1871, a young Chinese woman named Yut Ho lived in Los Angeles, though perhaps “lived” isn’t quite the right word. She survived—barely. The streets she walked every day, the crowded and dusty blocks of Calle de los Negros, were both her prison and her battleground.

Yut Ho, like many other Chinese women in Los Angeles at the time, hadn’t chosen this life. She had been brought to the city against her will, sold into sexual slavery by men who saw her as nothing more than a commodity. Chinese women were treated as pawns—something to be controlled, fought over, and exploited for profit.

Escape was almost impossible. Even if a woman managed to flee, the men who claimed ownership of her would come after her. And worse? Sometimes the police, the very people tasked with maintaining order, would help these men find her, dragging her back in exchange for a bribe. That was Los Angeles—a city rife with corruption, violence, and systemic exploitation.

But on this particular day, Yut Ho’s life would be thrust into the center of a storm. She had been kidnapped—or perhaps she had escaped, or forceable married to legally she “belonged” to a specific tong, though no one ever bothered to ask her side of the story. To the Hong Chow and Ning Yung tongs, what she wanted didn’t matter. To them, she was a prize, a source of power and profit, and her disappearance would ignite a feud that had been simmering for months.

The fight broke out in the streets of Calle de los Negros. Members of the rival tongs—both armed—exchanged gunfire in broad daylight. The shouting and gunshots echoed through the streets, drawing attention from the police & curious onlookers. People were wounded.

Enter Robert Thompson, a white rancher and former saloon owner, who decided to step into the chaos. Whether he thought he was keeping the peace or just couldn’t mind his business, one thing is clear: he escalated the situation. Armed and overconfident, he walked into a fight that wasn’t his to handle, despite being warned by multiple bystanders to stay back.

Thompson ignored the warnings, and fired shots into a building where a few of the tong members were hiding. Then, bold as ever, he entered the building, gun drawn, and whatever happened next remains murky. But as soon as he stepped through the doorway, bang bang, he was shot in the chest.

Bystanders carried Thompson to an apothecary nearby, but the damage was too severe. He died shortly after. Word of his death spread rapidly through the tiny town of Los Angeles.

Thompson wasn’t just any man. He was white, well off, and well-known, the kind of person who symbolized power and control in 1871 Los Angeles. His death wasn’t seen as the result of his own reckless decision to walk into a tong conflict armed—it was framed as an attack on the entire white community. Literally, people spread word that “the Chinese were taking up arms and killing whites.” To many, it was the excuse they’d been waiting for to lash out at the city’s small but growing Chinese community.

By nightfall, 500 people—nearly 10% of Los Angeles’ population at the time—had gathered, armed with guns, knives, and ropes. Most were white, but some were Mexican residents, drawn in by their own resentments toward the Chinese, often fueled by economic competition and years of anti-Chinese propaganda.

It’s wild to think about how quickly they mobilized, right? This started in the afternoon. Thompson died just a few hours later, and what—nightfall in October is around 6 p.m.? Atleast it is where I live. So, between lunchtime and dinnertime, 500 people were organized and armed, ready to commit heinous acts of violence against a community that made up just a tiny fraction of the city’s population. Another source said that the mob actually gathered like 2-hours later.

I really want to stress: this act wasn’t random. It also wasn’t a one-off, unique event. This mob, and all their hatred, didn’t form out of thin air. Years of anti-Chinese sentiment—stoked by systemic racism, economic fears, and a culture that normalized violence against people who represented “the other”, in this case, specifically the Chinese—had laid the foundation for this moment. Hatred like this doesn’t just appear overnight. But when it festers and boils over? It has the horrifying ability to bring people together in the worst way imaginable.

And this mob didn’t waste any time. Once organized they made their way to Calle de los Negros, and descended on the community with terrifying speed. Homes and businesses were looted, vandalized, and/or burned. People were dragged out into the streets and brutally attacked. I found a quote on the LA City Historical Society from one white witness, who reported:

News of the attacks and counter-attacks spread like wild-fire, 433 and a mob of a thousand or more frenzied beyond control, armed with pistols, guns, knives and ropes, and determined to avenge Thompson’s murder, assembled in the neighborhood of the disturbance. A Chinese man, waving a hatchet, was seen trying to escape across Los Angeles Street, and Romo Sortorel captured him. The crowd was yelling “Hang him! Shoot him!” He was dragged up Temple to New High street, where the familiar framework of the corral gates suggested its use as gallows. With the first suspension, the rope broke; but the second attempt to hang the prisoner was successful. Other Chinese men whose roofs had been smashed in, were rushed down Los Angeles Street to the south side of Commercial, and there, near Goller’s wagon shop, between wagons stood on end, were hung.

The mob was indiscriminate when it came to lynching—it didn’t matter if it was men or boys, they eagerly snatched anyone they could get their hands on. Some victims were lynched from lampposts, wagons, and hastily built gallows. Their bodies were left hanging as a message to the survivors.

You’d think that with 500 people descending on this community, the police would’ve stepped in to stop it. It is recorded though that a few officers & a couple of citizens did try to intervene. But they were either overpowered or ignored. Some accounts even suggest that certain police officers participated in the violence themselves.

By 9 p.m., nearly all of the Chinese residents who hadn’t managed to escape earlier in the evening had either been captured by the mob or found refuge in the city jail or with friendly shopkeepers and homeowners who offered them shelter. That part makes me feel some kind of way, like, not everyone was committing atrocities or idly watching them occur. It reminds me of the quote by Nancy, the mother of the infamous Mr. Roger’s, who would tell him when awful things happened: “Always look for the helpers. There will always be helpers”.

When morning came, the citizens of Los Angeles were faced with the horrifying aftermath of the night’s violence. The streets of Chinatown were littered with destruction, and survivors were left traumatized and terrified. Among the devastation were the bodies of 18 Chinese men and a boy, some mutilated in addition to being lynched, and all left on display for the entire world to see. Among the victims was Dr. Gene Tong, who had pleaded for his life, offering money to be spared, but his neighbors shot him in the face and then hung his body for all to see.

I can’t help but think about Billie Holiday’s haunting song ‘Strange Fruit.’ You know, the one that talks about bodies ‘hanging from the poplar trees.’ That song was written decades later, about the lynching of Black Americans, but the words echo here too, because the purpose of lynching was always the same: terror. It wasn’t just about killing a person—it was about sending a message. A grotesque, public display meant to dehumanize an entire community. And in this moment, that message was aimed squarely at Los Angeles’ Chinese residents: You don’t belong here. You’re not safe. And the law won’t protect you.

None of the victims had anything to do with the earlier shooting. Not a single person the crowd murdered was to blame. They weren’t involved in the tong feud or the fight over Yut Ho—they were just living their lives, trying to survive in a city that was hostile to their very existence.

The massacre shocked the nation. Newspapers from coast to coast picked up the story, and Los Angeles, in what feels like an obligatory move, launched a coroner’s inquest. Indictments followed, and eventually nine men were convicted of manslaughter. Justice, right?! Wrong. They received sentences of two to six years in San Quentin State Prison.

But here’s the kicker: a year later, all of them were released. Why? Because of some alleged “technical flaw” in the indictments. Ultimately, no one else was held accountable for the deaths or destruction caused.

For the survivors, some fled LA entirely, terrified that the violence would happen again. Others stayed, trying to rebuild in a city that had shown them, in no uncertain terms, that their lives did not matter.

By the time the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was passed, the community had already endured years of violence, discrimination, and isolation. The Chinatown we know today wasn’t created until the 1930s. The original Chinatown? It could never fully recover.

So, let’s talk about the aftermath of the Chinese Massacre of 1871—and what it says about justice, accountability, and the systems that allowed this violence to happen in the first place. Spoiler alert: this part isn’t any less infuriating than the massacre itself.

No one was held accountable. I mean, the trial was never about justice for the Chinese community. It was a performance. It was the city of Los Angeles saying, “Look, we’re doing something, we’re not monsters” when, in reality, they were doing the bare minimum. The legal system wasn’t designed to protect marginalized groups. The system was there to protect the mob—or at least the white majority that made up most of it.

Here’s another layer of frustration: the role of law enforcement. As I mentioned earlier, the police weren’t exactly heroes in this story. The massacre happened in plain sight, over the course of hours. This wasn’t a quick, uncontrollable riot. It was calculated, deliberate, and sustained. The police could have done more—they should have done more. But in a little frontier town, a town where anti-Chinese sentiment was normalized, the people tasked with enforcing the law sadly often shared the same prejudices as the mob.

If we zoom out, the lack of accountability for the massacre isn’t surprising when you consider the broader legal and social context of the time. In 1871, Chinese immigrants were legally not allowed to testify against white people in court under California law. Let that sink in. Even if there had been witnesses who could identify every single person in the mob, their voices wouldn’t have been heard.

This law wasn’t some outdated technicality—it was a deliberate tool to dehumanize Chinese people and strip them of legal protections. And it wasn’t unique to Chinese immigrants. Similar laws had been used to disenfranchise Indigenous people, African Americans, and other marginalized groups. It was part of a system that said, loud and clear: your life doesn’t matter as much as theirs.

And let’s not forget about the media, because newspapers played a huge role in stoking the flames of anti-Chinese hatred. Leading up to the massacre, local papers routinely published racist caricatures and editorials portraying Chinese immigrants as dirty, immoral, and a threat to society.

After the massacre, a lot of those same newspapers either downplayed the violence or straight-up justified it. They tried to spin the mob as “avenging” Robert Thompson, conveniently ignoring the fact that Thompson had absolutely no business inserting himself into the chaos. Like, he rolled up, guns blazing, acting like some Wild West hero, and basically got himself killed. He did that to him! Like this specific tragedy could of been avoided if he minded his damn business!

Even national papers that condemned the violence often did so in ways that still dehumanized the victims. They treated the massacre as a tragedy for Los Angeles, the place, not for the Chinese community. The narrative was less, “How could this happen to these innocent people?” and more, “Wow, that city looks bad.”

One of the most challenging parts of researching the Chinese Massacre of 1871 is the lack of consistent documentation. Wikipedia is my friend, but I also look for scholarly sources & first-hand accounts or like newspapers from the time. Some sources mention fires, while others don’t. Some accounts suggest women and children were also dragged out and beaten, but there’s no clear consensus. Some say the bodies were left naked and dangling, and mutilated, but not all accounts share that detail. It could also be my shotty research, in my rush and passion on the topic I wasn’t as thorough as usual. And I hope I’m not doing this traumatic event a disservice because that is not my intention.

Regardless, there were surviviors, atleast what…160-ish men, and the women and children, I imagine. But their voices are largely missing from this story—not because they didn’t exist, but because the legal and social systems of the time silenced them. I did see a few sources where Chang Wan, the wife of Dr. Tong, accused a Chinese man of inciting the violence (because she legally couldn’t accuse anyone white of anything), but it didn’t sound like anything came from that. This absence of accounts from the people directly impacted is a reminder of how systemic racism doesn’t just destroy lives; it erases them from history.

So, what does all of this tell us? It tells us that the Chinese Massacre of 1871 wasn’t just some one-off atrocity—it was the product of a much larger system of oppression. It showed us how power structures protect themselves, how justice is anything but fair, and how marginalized communities are left to fend for themselves in a world that’s actively stacked against them.

And here’s the thing: it’s still happening. Sure, the specifics might look different, we call it “Remain in Mexico”, or build structures and systems with the goal of keeping people out, but the blueprint hasn’t changed much. Immigrants are still scapegoated. Marginalized communities are still disproportionately targeted, and justice? It still feels like something that’s out of reach unless you’re on the “right side” of power. Laws might look different on paper, but the patterns—racism, xenophobia, inequality—they’re still here.

I want to share something personal here, and I just want to say upfront—I know my experience isn’t the same as what the Chinese community went through in 1871. But I do think it’s important to reflect on how these dynamics of being ‘othered’ play out in our lives, even today. For me, it looks a little like this: I’m mixed race, and I can’t even count the number of times I’ve been treated differently because of the way I look.

If you look at me, I’m what people like to call “racially or ethnically ambiguous.” Am I Black? White? Or maybe part of another group—Hispanic, Middle Eastern? Over the years, people have assumed I’m Cuban, Colombian, Puerto Rican, Italian, Arab—you name it. And let me tell you, that’s brought its own set of experiences.

Sometimes it’s harmless, like when someone assumes I’m from a certain region and starts speaking to me in its language. And there I am, deer-in-the-headlights, stumbling to explain that no, I don’t understand—but somehow I feel bad, like I’ve let them down for thinking I belonged. Other times, though, it’s not so harmless. Sometimes it’s ignorance, unwanted physical contact, hostility, or outright exclusion.

It’s strange, isn’t it? How something as basic as the way people perceive you—the box they think you fit into—can shape whether you’re treated as though you belong or as though you don’t. Social relationships and interactions are so fascinating.

Now, I know that’s not the same as xenophobia, but it has given me a glimpse into how these perceptions of ‘difference’, and of ‘other’—of who’s in the group and who’s not—can shape a person’s entire life. And it’s definitely shaped mine.

And here’s the thing: at the heart of what happened in 1871 was this very idea. The Chinese community wasn’t seen as part of the group. They were scapegoated, vilified, and dehumanized because they were considered outsiders—‘others.’ When a society normalizes those kinds of assumptions—when being different is seen as a threat—it opens the door for fear, hatred, and violence to take root.

Let’s look at right now. It’s 2025, and we’re watching policies roll out that feel like echoes of this same history. I’m sitting here, upside-down smiley face emoji-ing, like seriously guys, we’re doing this again? The majority of you are really ready to do this…again? BECAUSE ITS WORKED SO WELL IN THE PAST.

….deep breath.

Immigrants are being cast as the enemy, just like the Chinese immigrants in 1871. Mass deportations, the end of birthright citizenship, and forcing asylum seekers to wait in Mexico—it’s all about creating an “us versus them” narrative. These policies don’t just enforce borders; they enforce fear, dehumanization, and the idea that some people don’t belong.

What happens when communities are treated this way? Families are torn apart. People live in constant fear, afraid to even step outside their homes. Workers are exploited because they can’t afford to demand better treatment—they’re too scared to make waves. Survivors of violence don’t report their trauma because they don’t trust the system to protect them.

That’s what happened to the Chinese community in 1871. And it’s what’s happening to immigrant communities today—mothers terrified they’ll be ripped away from their children, workers vilified just for existing, neighbors branded as criminals just because they wanted a better life.

And much like in 1871, it’s not about individuals—it’s about targeting entire communities. These policies send a message: You’re not safe. You’re not welcome. You don’t matter. Just like the mob in Los Angeles, these actions are fueled by fear and hatred, designed to maintain power for some by keeping others down.

The thing is, hatred like this doesn’t just appear out of thin air. It takes time. It’s stoked. And if you zoom out, you can see the same story repeating over and over again. In 1871, the Chinese were scapegoated as job-stealers, dirty, and dangerous outsiders. In the 1930s, it was Jewish refugees fleeing Europe. In the 1940s, Japanese Americans were thrown into internment camps. And today, it’s Central American migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees. The names and faces might change, but the playbook? It stays the same.

And every time, we look back and ask: How could we let that happen? But here’s the real question: What are we doing right now to make sure we’re not the next chapter in that playbook? Because every time we choose silence, every time we look the other way, every time we choose not to get involved, we’re letting it happen again.

Here’s the thing: scapegoating immigrants has never been about solving actual problems. It’s about power. It’s about distraction. It’s about giving people someone to blame so they don’t look too hard at the real issues—things like wealth inequality, obvious and hidden corruption, or systemic exploitation. And while politicians stir up fear and pass these laws, there are people profiting from it. Corporations exploit immigrant labor for pennies on the dollar. Politicians score points with their base by blaming society’s problems on “outsiders.” And the systems that thrive on division? They just keep getting stronger.

So, when we look back at 1871, we can’t just say, “Wow, that was a terrible thing that happened.” We have to ask: How much has really changed? Are we still repeating the same mistakes? Are we still letting fear and hatred divide us while the real issues go unchecked?

Because history isn’t just about the past—it’s about what we do next. It’s about whether we keep repeating the same mistakes or whether we finally, finally choose to do the hard work and break the cycle.

So, where do we go from here? The Chinese Massacre of 1871 wasn’t just a horrific event—it was a warning. A flashing neon sign telling us exactly what happens when fear, hatred, and unchecked power collide.

And it’s so easy to think, “That was then. That could never happen today.” But history isn’t some dusty museum piece. It’s alive. And if you take even a second to look around, you’ll see it repeating itself in real time. The question isn’t whether the echoes of 1871 are still here—it’s whether we’re actually paying attention.

Because here’s the truth: silence is complicity. But every single one of us has the power to make noise, to break cycles, and to write a different story. So don’t let this story fade into the background. Share it. Talk about it. Learn from it. Let it remind you that silence is never neutral—and history will absolutely repeat itself if we let it.

So where do we start? Support organizations like RAICES or the ACLU that are fighting for immigrant rights every single day. Get to know your local immigrant communities—their stories, their struggles, their contributions. I promise, you’ll learn something that will surprise you and probably make you feel deeply connected. Because guess what? We are connected, whether we like it or not.

And most importantly? Push back. When someone in your circle starts spouting anti-immigrant rhetoric, don’t stay silent. Speak up. It doesn’t have to be perfect or confrontational. Ask questions like, “Why do you think that?”, or “Why do you think it’s ok to say that?” or “What would you do if you were in their shoes?” Share facts, like how immigrants actually contribute more in taxes than they take in benefits. And if nothing else, set boundaries—“I’m not comfortable with that kind of talk.”

The most important thing is to say something. Because every time we stay silent, harmful ideas take root. And we already know exactly where that can lead.

As we wrap up, I want to bring us back to something I mentioned at the start of the episode: Chinese Lunar New Year. This Wednesday, families all over the world will come together to celebrate, just as they’ve done for centuries. It’s a reminder that no matter how much a community is tested, their traditions, their strength, and their resilience endure.

The Chinese community of 1871 deserved better. And today, immigrant communities all across the country deserve better. But what gives me hope is that resilience. Traditions like Lunar New Year are proof that even in the face of unimaginable hardship, culture and community survive—and thrive.

Thank you for being here with me today. I hope this story stays with you—because it’s not just a piece of the past. It’s a mirror. And maybe even a map, showing us exactly where we’re heading if we’re not careful.

Until next time.

Be kind. Be curious. And be ready to make history.

Interested in learning more? We recommend:

- “The Chinese Must Go: Violence, Exclusion, and the Making of the Alien in America” by Beth Lew-Williams,

- “Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans” by Jean Pfaelzer,

- “The Making of Asian America: A History” by Erika Lee,

- The PBS Documentary: “Becoming American: The Chinese Experience”.

And find more resources and stories like this on our website, www.bygoneechoes.website