Idora Park: Trolley Park Thrills and Ghost Coaster Chills

TLDR; Kid stumbles upon a rusty old roller coaster in the woods, sparking a total "where's my mystery van?" moment. Digs into the history of trolley parks, like Idora Park, basically the 1900s version of Disneyland minus the mouse. These parks were where everyone hung out before Netflix and chill. Idora was all fun and games until it wasn't. Economic downturns and a "this is fine" meme-worthy fire in '84 turned it into ghost park central. It's a roller coaster ride of history, with a side of nostalgia and a dash of mystery. 🎢🔍🌳🔥👻😂 Park Map circa 1980

Park Map circa 1980 Source - Danso

Source - National Archives

Source - Mahoning History

Infamous French Fries Stand

Infamous French Fries StandSource - Idora Park

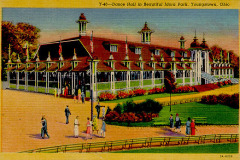

1920 Dance Hall Postcard

1920 Dance Hall PostcardSource - Wikipedia

Mahoning History

Eamon de Valera, a key figure in Ireland’s fight for independence, captivated the audience in the Idora Ballroom.

Eamon de Valera, a key figure in Ireland’s fight for independence, captivated the audience in the Idora Ballroom. Source - Business Journal Daily

The Idora Ballroom, circa 1958

The Idora Ballroom, circa 1958Source - Mahoning History

Source - Idora Park

Idora Park Midway

Idora Park MidwaySource - Mahoning History

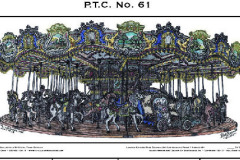

Idora Park Carousel Graphic

Idora Park Carousel Graphic Source - Business Journal Daily

Idora Park Carousel Colorized Photo

Idora Park Carousel Colorized PhotoSource - Idora Park

Transcript

Picture this: a crisp fall day, the kind where the air is fresh and the leaves crunch underfoot. I’m just a kid, out for a family walk at our local metro park. We decide to try a new trail, a path less traveled, brimming with the promise of adventure.

As I rush ahead, curiosity-fueling my steps, the trail comes to an abrupt end, closed off. But something catches my eye through the thinning trees – a flash of rusted metal. There, amidst the serene greenery and babbling streams of the park, stands a roller coaster, its frame stark against the natural backdrop.

I’m perplexed, my mind buzzing with questions. How? Why? I squint, trying to make sense of it, the image of the coaster imprinted in my curious mind. I call out, “What is that?” But my voice is swallowed by the distance as my family, retracing their steps since the trail has ended, doesn’t hear me. I hurry to catch up, my head swirling with thoughts.

As we walk back, my imagination takes flight. It’s like an episode of Scooby-Doo, a mystery waiting to be unraveled. When I later ask about it, no one seems to know what I’m talking about. That image of the roller coaster, shrouded in the park’s natural beauty, stays with me, a daydream that occasionally revisits me, a puzzle piece from my childhood still waiting to fit into the bigger picture.

Hey there, and welcome to “Bygone Echoes”! Today, we’re time-traveling to the heyday of America’s trolley parks, those magical spots where fun and transport magically merged. Think late 1800s to early 1900s, when these places were the heart and soul of communities, thanks in part to the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. These parks were more than fun zones; they were emblems of innovation, communal spirit, and pure American joy.

Take Idora Park in Youngstown, Ohio, for example. What was once a hub of happiness is now a forgotten relic. Starting as a simple picnic spot, Idora grew into an enchanting realm filled with thrilling rides and dance halls, crafting memories that were meant to last forever. But time can be unkind, and today, Idora’s glory is just a whisper of the past.

My own encounter with Idora was through its eerie quiet, not the lively bustle it once knew. Discovering its ghostly remains sparked a blend of curiosity, mis-remebering and a longing for a bygone era. The decaying park, now reclaimed by nature, seemed to murmur stories, blurring the lines between fantasy and reality.

People are drawn to places like Idora for their mystery, nostalgia, and the thrill of exploration, not to mention their haunting beauty and historical allure. But hey, if you’re venturing into such spots, always remember to keep it safe and legal.

So, come along as we delve into the rise and fall of trolley parks like Idora, weaving through the tales I imagined and the truths I unearthed. Let’s wander through the life and quiet afterlife of these once jubilant places, where now only memories linger. Let’s start this adventure!

Step back to the Industrial Revolution, a time of dramatic urban transformation. Smokestacks defined city skylines, while environmental concerns were barely an afterthought. People flocked from the unpredictable rhythms of countryside farms to the city’s bustling factories, drawn by the allure of a stable, albeit demanding, urban life.

This urban migration sparked a novel concept: leisure time. Weekends transformed from mere days off to cherished moments of personal freedom, essential for well-being. City dwellers, however, had limited leisure options, often confined to local town squares, nature spots, or small community gatherings. Travel and large-scale entertainment were luxuries few could afford.

A significant change arrived with the electric trolley in 1888. More than just a new mode of transport, it revolutionized city life. Trolleys connected diverse neighborhoods and made distant suburbs accessible, reshaping how people interacted with their cities and leisure time.

This era birthed the trolley parks, charming precursors to modern amusement parks. Nestled at the end of trolley lines, these parks emerged as popular escapes, offering a blend of fun and freedom. The story of the trolley and trolley parks marks not just a transport evolution but a pivotal shift in social dynamics, setting the stage for the public transportation systems and urban leisure culture we know today.

Imagine a bright, early summer morning, you’re riding a trolley, its bell’s chime still echoing as you disembark at a trolley park, buzzing with a unique enchantment. The air is electric with excitement, mingled with the sweet aromas of popcorn and cotton candy.

These parks were vibrant mosaics of life and laughter. Picture lush picnic spots, alive with the joyous noise of families and friends. There’s music in the air – live bands setting the tempo, their tunes painting this scene of social gaiety. And oh, the dance halls! They’re a swirl of colors and sounds, with laughter reverberating to the rhythm of catchy melodies.

But the rides were the real showstoppers. Roller coasters, like dragons from fairy tales, twisted and turned into thrilling dances. Carousels, adorned with ornate horses, spun in a vibrant whirl, their calliopes playing heart-stirring tunes.

These trolley parks were more than playgrounds; they were festivals for the senses, rich tapestries of experiences. They reflected the era’s bright-eyed optimism, a slice of America’s burgeoning romance with leisure and innovation. Here, communities bonded, interlaced by the shared joy and wonder, crafting a beautiful collage of collective memories.

Let’s step into the late 1890s Youngstown, Ohio, a bustling hub of industry and innovation. This era, transitioning from the Gilded Age’s opulence to the Progressive Era’s social reforms, reshaped America. The impacts of these reforms in enhancing working conditions, civil rights, and equitable society still resonate in American policy and politics today.

Youngstown was more than a city; it was a cornerstone in America’s steel story. Its prime location, blessed with railroads and the Mahoning River, positioned it as a steel-producing titan. From the 1800s to the 1970s, Youngstown’s steel was integral to the growth of U.S. cities, supporting everything from construction to the automotive industry.

The city’s steel boom nurtured a rich cultural and social tapestry, thanks to its diverse communities – African American, Eastern European, Italian, and more. Youngstown thrived with social clubs, churches, and cultural festivals, a vibrant testament to community spirit.

Amidst industrial growth, Youngstown recognized the importance of green spaces. Thus, Mill Creek Park was created, a natural oasis with cascading waters and lush landscapes. In its heart stands the historic Lanternman Mill, dating back to 1845, still operational in summers. This park, a backdrop to my childhood memories and local lore, even boasts landscaping by the same firm that worked on the Columbian Exposition.

During this time, the Park & Falls Street Railway Company emerged, connecting the city with its transport services. Spotting an opportunity on the city’s south side, they, like many trolley companies of the era, developed a leisure destination to boost ridership. This led to the birth of Terminal Park.

Strategically located near Mill Creek Park, Terminal Park was an escape from the industrial smog, situated about 3.5 miles from Youngstown’s Central Square. This distance encouraged people to take the convenient trolley, costing just a nickel, to the park, which offered free admission – a clever strategy to attract visitors and enhance city life.

What relics of your own town’s past have you stumbled upon, and how did they make you feel about the passage of time?

This amusement destination started as a modest 7-acre wonder and grew to an enchanting 28 acres. Snug next to Mill Creek Park, on the city’s edge, it was a captivating story with limited space to expand.

Architecturally, the park was a mixtape of styles – Colonial Revival chatting with sleek Moderne and elegant Italianate. In its opening season, it was a treasure trove: a bustling casino, a vibrant theatre, a bandstand full of music, sky-touching swings, and all the essentials like fountains and restrooms. And the star attraction? A whimsical electric Merry-Go-Round, boasting Gustav Dentzel’s beautifully carved animals. The park soon added a midway, sprinkling more fun with games and snack stands.

Opening on Decoration Day (now Memorial Day), May 30, 1899, Terminal Park, as it was first known, was an instant crowd-pleaser. By its second season, it transformed into Idora Park. But the name’s origin? That’s a charming puzzle. Some say a local teacher named it in a contest; others think it’s a playful twist on “I adore a park.” There are even hints at a connection to the so-called Idora Falls in Mill Creek Park. But really, the true story is lost in a delightful fog of myths.

Name aside, Idora Park became synonymous with joy, a vibrant chapter in Youngstown’s community story. More than a park, it was a symbol, a collective memory, a resonance of laughter and joy, echoing through time and change.

Can you imagine how a visit to Idora Park might have felt during its golden age? Idora Park, dubbed “Youngstown’s Million Dollar Park,” was a melting pot of joy, attracting people from all walks of life with its affordable fun, especially during the tough times of the Great Depression and World War II.

Rapidly evolving under changing management, Idora was abuzz with fresh attractions. It featured a grand dance pavilion, a lively vaudeville theater packed with burlesque, comedy, and song-and-dance acts, and a bandstand perfect for lazy afternoons. Visitors were treated to sky-high swings, peaceful picnics in shady spots, and an array of refreshment stands. Among these, the famously irresistible french fries became a signature scent of the Idora experience, adding to its unique charm.

At the southwestern end of Idora Park stood the ballroom, a centerpiece in the park’s symphony of growth. Beginning as a modest dance hall, it transformed into the majestic “Idora Ballroom” by 1910, thanks to architect Angus Wade. Blending Moorish, Italianate, and Neoclassical designs, this ballroom boasted a sprawling 30,000 square-foot dance floor, rivaling even Coney Island’s famous pavilion. For a period, the ballroom also transformed into the Idora Roller Skating Palace.

The ballroom’s walls resonated with a diverse array of talents. Legendary musicians like John Philip Sousa and Cab Calloway, and political figures such as JFK and Richard Nixon, all graced its stage. A standout moment was in 1919 when Eamon de Valera, a key figure in Ireland’s fight for independence, captivated audiences with his fervent call for freedom.

Music was the heartbeat of Idora, shifting from Sousa’s 1918 anthems to the Big Band era with stars like the Dorsey Brothers and Benny Goodman. As rock and roll surged in the 50s and 60s, Idora smoothly transitioned, hosting modern legends like The Eagles and The Monkees, yet still holding onto the charm of polka bands.

Reflecting Idora’s adaptability, the 1950s saw the ballroom undergo a makeover, shedding its Moorish elements for a contemporary look, a testament to the park’s enduring spirit of evolution.

Right north of the ballroom lay Idora Park’s buzzing midway, home to a plethora of rides and attractions like the Ferris wheel, fun houses, bumper cars and arcade games. The northend of the Upper Midway housed attractions like the “Monkey Island”, an exhibit of various monkey species, naturalistic settings offering a blend of entertainment and education for park visitors.

But let’s zoom in on the roller coasters, the heart of the thrill here. It all started in 1902 with a figure-eight toboggan slide, later replaced by the Firefly in the 1920s and eventually by the legendary Wildcat.

The Wildcat, debuting in 1930, was a yellow 85-foot high, 3,000-foot-long wooden coaster, famed for its airtime, intense fan turn, and lateral forces. Its unique feature? No restraints, offering a wildly exhilarating ride. It was still a top ten roller coaster in the early 1980’s, renowned for its large size and innovative, twisting track.

Then there was the Jack Rabbit, a gentler yet iconic wooden coaster with a unique “figure-eight” design. Built in 1910, it stood 70 feet tall and 2,200 feet long, offering a 2.5-minute ride. Both coasters were pivotal in the park’s charm.

For the little ones, there was “Kiddieland,” filled with fun child-centered attractions and miniature versions of the bigger rides.

Near the midway’s west side stood the merry-go-round, and here’s my favorite – the carousel! The original carousel, moved out in 1922, made way for the Idora Park Merry-Go-Round. This classic, antique carousel featured 48 intricately carved and vividly painted horses and two chariots. Its craftsmanship and ornate brass poles radiated timeless elegance. A rare gem, it was one of only 87 made by the Philadelphia Toboggan Company.

In 1924, Idora Park unveiled a luxurious addition, creating waves of excitement: a grand swimming pool, fondly called the ‘Natatorium.’ Picture this: a vast circular pool, its edges graced with sand shipped from Atlantic City. But the real surprise? The water was salty, mimicking the ocean, thanks to an unexpected salt deposit beneath the park. Advertisements celebrated this as a seashore experience right in Youngstown.

Idora Park’s history is rich with diverse tales and contrasting memories. From urban legends, like the 1938 snake bite incident on the Wildcat coaster, to contrasting accounts of inclusivity and racial discrimination, the park’s past reflects the complexity of societal narratives.

Reflecting on Idora Park through the lenses of different eras, we see a vivid contrast in experiences. First-hand accounts of white residents from the late ’80s and ’90s recall an inclusive haven, while Black community members share memories tinged with racial discrimination. This striking contrast underscores the importance of embracing diverse narratives to fully comprehend our history.

In 1948, Idora Park removed its pool to expand KiddieLand, igniting a debate. Given national calls for racial integration in swimming pools, it prompts questions: Was it an attempt to evade pool integration or a response to local needs? These questions underscore the complexity of historical events.

Adding rich layers to this story are personal accounts. One from Joseph, who worked at Idora as a teenager starting in 1936, details his journey through military service, family life, and trade work, reflecting resilience and adaptability. Melissa’s 1936 story, a woman in her 80’s living in Youngstown who was born into slavery. She offers insight into her life, born on a Georgia plantation, her post-emancipation struggles, and the move north for family and freedom.

These narratives, set against a backdrop of racial inequality and societal change, are powerful reminders of the diverse and resilient human spirit that shaped these times.

However, alongside the triumphs and personal journeys, tragedies are also an integral part of Idora’s story. In 1929, a high school senior tragically lost his life on the Jack Rabbit coaster. The summer of 1944 was marred by several drowning incidents. In 1948, a 20-year-old man fatally fell from the Wild Cat, and in 1963, a 16-year-old boy met a tragic end on the Jack Rabbit. These somber events serve as a sobering reminder of the fragility of life, even in the midst of vibrant amusement and personal resilience.

Adding to Idora’s unusual history, 1947 saw fourteen monkeys escape; some were shot for safety reasons, while others vanished into nearby Mill Creek Park. This incident surprisingly connects to my childhood. My cousins warned me about monkeys in Mill Creek Park – a piece of lore I never understood until researching Idora. Joseph worked at Idora at the time, and recalled “They had a smaller version of Monkey Island and moved it over by the Kiddie Land. Then they tore it down. The monkies kept getting out. They were afraid they were going to cause some trouble so they just did away with it.”

Idora Park’s story, once vibrant, turned into a somber chapter as it faced its inevitable decline and closure. Despite evolving with the times, it couldn’t withstand changing entertainment preferences, the allure of modern attractions, and Youngstown’s economic struggles.

The city’s downfall, closely tied to the steel industry’s collapse, brought job losses, population decline, and urban decay, impacting Idora deeply. The park, once thriving on company picnics and community events, struggled as its core working-class audience diminished, and larger amusement parks like Cedar Point, and King’s Island drew crowds away.

As the park’s clientele shifted more towards youngsters and teenagers, rock concerts replaced big bands in the ballroom. Financial struggles led to a sale attempt in the early 1980s, but tragedy struck before a buyer emerged. In 1984, a catastrophic fire ravaged Idora, including the iconic Wildcat coaster, marking a tragic end.

Idora closed in September 1984, and its remains were auctioned off. The park was further diminished by subsequent fires, and the remaining structures were demolished in the early 2000s. Unfortunately, no real attempts were successful in preserving this icon. How do you think communities should preserve their historical landmarks in the face of modern challenges? What does the fall of such cultural landmarks tell us about the changing face of entertainment and community values?

The loss of Idora Park left a profound void in the Youngstown community. More than just a place, it was a part of the city’s soul, a backdrop to generations of memories. Its absence was mourned like a lost friend, leaving a legacy of joy, community spirit, and bittersweet nostalgia.

In the 1920s, Idora Park, along with other streetcar parks, reached their peak. From about 2,000 amusement parks in 1920, the number dwindled to just 303 by 1935, largely due to the rise of automobiles. Today, only 12 remain. Idora Park, however, outlasted many peers, adapting to changes like the popularity of cars and movies. Its survival was thanks to innovative attractions and the steel industry’s frequent company events.

Although it’s no longer open, Idora Park continues to hold a special place in Youngstown’s heart. It’s remembered not just as a historical site, but as a symbol of community, joy, and collective memories. It was a place where many shared unforgettable experiences.

Local efforts to preserve Idora Park’s legacy are evident, with memorabilia displayed in ‘The Idora Park Experience’ museum. The park’s famous carousel, was purchased in the 1984 auction and was lovingly restored by artist Jane Walenta, over 100 years later it now brings joy to visitors in Brooklyn, NY.

My childhood memory of seeing the skeleton of a roller coaster while on a family walk sparked my journey to unravel the mysteries of Idora Park, its historical significance, and its place in our society. It’s turned out to be a treasure trove of stories waiting to be discovered, and for me, that’s the true treasure of this adventure.

Thanks for tuning in and taking a ride through history with us! While uncovering Idora Park’s history, we find its essence not just in thrilling rides or dance hall music, but in the joy and connections it created, symbolizing the beauty of community and simple pleasures. Yet, embracing both its highlights and shadows reveals its true complexity. Idora’s tale, with its mix of inclusivity and exclusivity, offers a nuanced view of history, reminding us to appreciate the good while learning from the challenges.

And speaking of intriguing tales, get ready for a spine-tingling journey on the next episode of Bygone Echoes where we’re listening to the Whispers in the Dark, exploring The Mystery of the Servant Girl Annihilator. It’s a story shrouded in mystery and darkness, waiting to be unraveled. So, stay tuned for another captivating episode where history’s echoes come alive!

Interested in learning more? We recommend:

- Hidden History of Youngstown and the Mahoning Valley by Sean T. Posey.

- Images of America. Youngstown by Donna de Blasio.

- Images of America. Lost Idora Park by James and Tony Amney.

- The Youngstown State University Oral History Program.

And visit our website at https://bygoneechoes.website/ for more resources.

Footnote

This is the inaugural item we’ve researched, so the documentation is somewhat lacking, but on the brighter side, at least everything is present.

Images

- Abandoned Idora: https://www.themeparkreview.com/idora/idora.htm

- Google Location Photos of Idora: https://www.google.com/travel/entity/key/ChUI9MGamoaNvZRZGgkvbS8wY19qY2YQBA/overview?utm_campaign=sharing&utm_medium=link&utm_source=htls&ts=CAEaBAoCGgAqBAoAGgA

- Ridezone Idora Images: http://www.ridezone.com/defunct/parks/OH/Idora/idora.htm

- Jane’s Carousel: https://janescarousel.com/

- Salem Library Historical Society: https://archive.org/details/salemlibraryhistoricalsociety?query=idora

Videos Clips

- Softball at Idora Park: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qRGbr3Zr-mg

- Got a Date with an Angel: Musical Memories of Idora Park: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MAsAZG2pGTY

- Idora Park pre-1950s film footage: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZKE0WDpcNyc&t=503s

- Idora Park by Mahoning History: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b0pTZpD6cGE

- Idora Park by The Laneman: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ufrk2V83c8I

- Idora Park Then and Now: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gy-JtggDZhE&t=41s

- Remembering Idora Park: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ePZ41ETr_BU

- Idora Park: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qbjPAM65AvI

Books

- DeBlasio, Donna M. Youngstown: Postcards from the Steel City. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2003.

- Scarsella, Richard S. Memories and Melancholy: Reflections on the Mahoning Valley and Youngstown, Ohio. Self-published, iUniverse, 2005.

- Shale, Rick. “The History of Idora Park (1899—1984).” Mahoning Valley Historical Society. April 26, 2014. Accessed November 26, 2018. https://mahoninghistory.org/2014/04/26/the-history-of-idora-park-1899-1984/

- Skrdla, Harry. Ghostly Ruins: America’s Forgotten Architecture. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006.

Websites

First Hand Accounts

- Riding the Wildcat Rollercoaster (Reddit)

- Youngstown State University Oral History Program

- Life on the Midway

- Anthony Renaldi – Wildcat

- Roy Platt – Idora Park Management

- Small Town Memories

- Brooklyn Magazine – Jane’s Carousel

Newspaper Clips

- The Vindicator: Idora Ballroom Chronology

- The Vindicator: Making headlines for 150 years

- 1948 – Wildcat Death

- 1948 Wildcat Death – Settlement

- WFMJ -100 Years Ago Today

- WKBN – 35 Years Since the Idora Park Fire

- 1963 – Jack Rabbit Death

- 1929 – Rollercoaster Death at Idora

- The Vindicator: 1913 – Idora Casino Opens

- The Vindicator: 1982 – Idora Park for Sale

- The Vindicator: 1903 – Idora Park Free Concerts

- The Vindicator:1986 – Memories and Landmarks Lost

- The Vindicator: 1902 – Fine Looking Crowd at Idora Park

- The Vindicator: 1999 – 100 Years of History, Idora Park

- The Vindicator: 2022 – Memory Lane May Close